America - The Covenant Nation

A Christian Perspective

Volume 1

To the Great Depression of the 1930s

For an extensively pictorial version of this same American history, go to my website, spiritualpilgrim.net. It was designed to be consulted in accompaniment with the reading of this historical series (this website ... and the actual published or text versions).

Preface

Introduction

1. Colonial Foundations

2. The Colonies Mature

3. Independence

4. The Birth of the American Republic

5. The Young Republic

6. The Shaping of a Nation

7. Expansion ... and Division

8. The Gathering Clouds of War

9. Civil War

10. America Recovers

11. The "Gilded Age" of American Capitalism

12. American Progressivism

13. The Rationalizing of Western Culture

14. Nationalism, Imperialism, and the Great War

15. The "Roaring Twenties"

16. The Great Depression

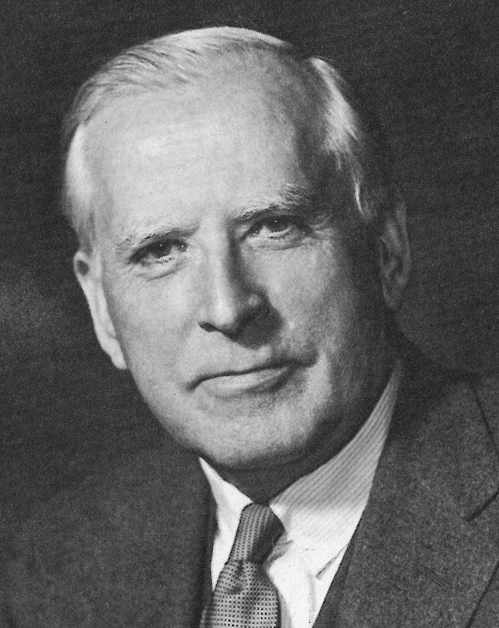

Excerpt 1. Washington – the warrior (pages 122-125)

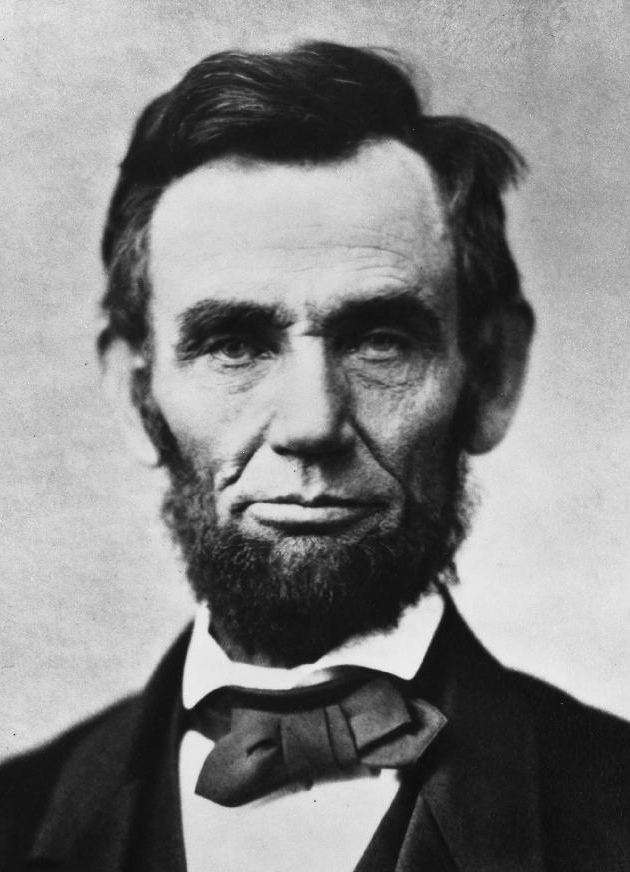

Excerpt 2. Lincoln the Christian (pages 288-289)

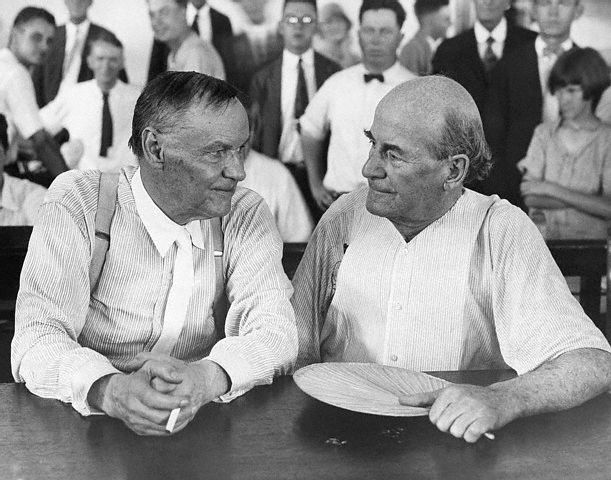

Excerpt 3. The Scopes Monkey Trial – 1925 (pages 483-485)

The Four Generations Theory. Societies inevitably rise and fall ... largely because of an internal dynamic that haunts all societies, something I describe in a parable – The Four Generations Theory – that I first developed back in the early 1970s as a young university professor, when asked the question by my students as to where I thought America was headed ... in terms of its own growth-and-decline dynamic.

Generation One is the society as shaped by a dynamic, highly self-disciplined, and quite charismatic leader, who is able to bring from relative social hardship, then ultimately to unity and full power, a group of very enthusiastic society builders, conquerors actually. Generation Two is led by the son of the Generation One leader, an individual broad in vision with strong administrative talents – able to bring to unity and strength a larger civilization that his father's band of warriors has just brought under his family's dominion. Generation Three is led by the palace-born aristocrat, son and grandson of the two generations before him, who has seen little of the hardships that the previous generations went through to put him in that palace ... but has grand ideas about bringing his very privileged world to perfection – at a grand cost economically to the masses of his society, who themselves will gain little personal advantage from all these fancy endeavors. Generation Four is the final generation, led by an individual who has no sense of social right or wrong ... but who has allowed himself to be led by socially undisciplined instincts that will degrade not only himself but also the society that is suffering enormously under his miserable "leadership," a society that is deeply vulnerable to being overrun by some outside group – led by a rising Generation One individual. Thus the cycle of birth, growth, maturity, decline and social death will repeat itself!

Why does human life even exist at all? Great thinkers, the ancient Greeks down to modern quantum physicists, have long pondered this same question. The universe is vast … yet as far as we know, the only part of Creation that is even slightly aware of its own existence is found only on this tiny speck of Creation – our earth. Therefore, there seems to be something very special about the distinct privilege of being alive, being human … even if only for a season.

The Judeo-Christian tradition. But why this privilege? The Judeo-Christian or Biblical tradition claims to have long understood the answer to that very question. According to this religious tradition, human life exists as sort of an "audience" to Creation. The Creator wanted some self-aware part of Creation to be able to join with its Creator in celebrating the wonder, the beauty, of it all. To do so would be to "glorify" Creation … make it come "alive" – well beyond just its mere existence.

And in that "joining" with the Creator, with Yahweh, with God the Father of it all, we humans became more than just things wandering around on this planet. As Jesus himself expressed things, we would come to the awesome understanding of ourselves as sons and daughters of this Most High God. God himself would be understood to be our true, our eternal, Abba or Daddy. That's quite an attachment to Creation, and with the Creator himself!

Mystics of all sorts of cultures and times have come to something of the same conclusion … as they have sought to become "one" with the world about them. But for Christians, the path to that oneness was no longer a question to be pondered … but instead a path already well understood. Jesus personified that path … so that those who followed his lead would complete their assigned purpose in being given the privilege of life.

Christians also have long understood this relatively brief time of life on this planet as something of an internship or an apprenticeship for something that followed life on this planet: our fellowship in the realm beyond Creation with God himself … for all eternity. It was sort of like life in the womb for a baby … part of its preparation for something yet bigger that laid beyond the womb.

But why would Christians believe in something, such as Eternity or Heaven, that no living person has ever seen personally? Why should anyone in their right minds begin to believe something that has no visible proof to us living here on earth. Don't we just die … and become food for worms? That's why Jesus's resurrection was so very, very important to Christians. In God as Father sending Jesus his Son back from his death on the cross … for at least 40 days and to at least 500 or more witnesses, God was putting before us earthlings the proof we would need to believe. But again, it would require belief … not just on the part of those 500, but also on the part of those after them that would believe their testimony.

But such belief was what ultimately made Christianity stand out – way out – beyond all other understandings of the times … in Judeo-Roman times – down to today. It is certainly what made Christians stand out among the citizens of those first-century days … when Christians sang hymns as they faced death in the arenas, deaths designed by the Roman authorities to entertain the masses.

But the Christian witness did more than entertain. It changed the lives of others.

The Call to be a City on a Hill … a Light to the Nations. This points to the fact that Christianity has always been more than just a personal path to greatness … and eternal life for the person of faith. For those who have been "elected" by God to a life of such Christian faith, they have also been commissioned by God to show others the way to the same sonship and daughtership that they enjoy with God as their Father.

Jesus himself made it clear that those so elected or "called" were to serve as apostles (Greek for "ones sent out") or missionaries – to use the more modern term. Christianity was not just a privilege for themselves alone. It was a call to greater service … to help bring all human life to have a successful "internship" in this life – and thus to find "salvation."

For Christians, the matter of what happened to souls who were not able to be reached by the "gospel" (good news) of Jesus and his ministry was problematic. So there was an urgency to the commission to preach to all the nations. But Christians also knew that God had other means to achieve whatever he wanted concerning human life. And therefore, they were to leave such matters as salvation to him. Nonetheless, their commission was clear – and urgent: preach the good news wherever/whenever possible.

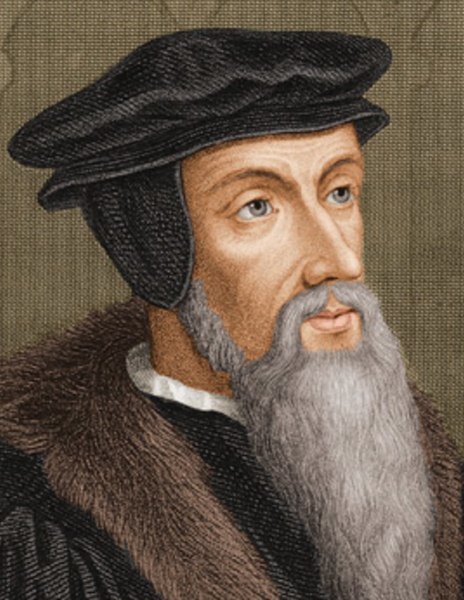

Calvin's Geneva sets the example. John Calvin put new life into Christianity when in the mid-1500s he "reformed" the city of Geneva along the lines of what the Bible refers to as a "City on a Hill," a "Light to the Nations. Europeans from every country flocked to Geneva to see what was happening there.

Calvin's Geneva sets the example. John Calvin put new life into Christianity when in the mid-1500s he "reformed" the city of Geneva along the lines of what the Bible refers to as a "City on a Hill," a "Light to the Nations. Europeans from every country flocked to Geneva to see what was happening there.

Here was a society that freely chose its own leaders, affirmed and reaffirmed on a regular basis … no longer a society living under the absolute sovereignty of some princely family which controlled all social life, not just politically but also economically, culturally and spiritually. In Geneva that kind of sovereignty belonged to the citizens of the city themselves … all of them on an equal basis.

And the reason that Geneva was headed down that road was because what was driving this dynamic was the clear directions that God had given humankind through Jesus himself: the critical understanding that we all stood as equals before God – loved by him on an equal (and quite full) basis … as a very good father would. Thus the social duties and rights or rewards that God assigned his children were also to have an equal standing in the earthly or human social realm … in line with Christian gospel standards. Consequently, these equal rights and duties together became the social "disciplines" that shaped Geneva into a powerful social enterprise.

This was the kind of democracy that had not been seen in Europe for centuries. Thus it was little wonder that multitudes of "middle class" Europeans flocked to Geneva to see what was going on there. Awesomely, Geneva was serving as God's "City on a Hill," his "Light to the Nations" … precisely as God wanted his people to live and flourish. Those that flocked to Geneva included numerous English … who were so impressed by Calvin's reforms that they returned to England hoping to see those same social-moral-spiritual reforms put in place in their home country.

It is extremely important to note that from its very outset, English America laid out not one but two distinct social traditions ... based on two very different reasons for coming to America. Basically these two distinct social traditions were focused on two different parts of the English settlement along the Atlantic coast.

The first of these is the Southern or Virginia tradition, first laid out in 1607 with the founding of the English settlement at Jamestown (Virginia). The second of these is the Northern or New England tradition laid out 15 to 20 years later (1620s and 1630s) in Plymouth and Boston (Massachusetts), Providence (Rhode Island) and Hartford (Connecticut).

Both settlements – which were quite different from each other in cultural character and consequently in political design as well – were shaped deeply by the European social contexts from which they were drawn. Both groups came out of a long-standing "Christian" social-cultural tradition. However that social-cultural mix had wide differences in character, differences which were reflected in the enormous differences distinguishing Virginia and New England.

Traditional-feudal Virginia. Virginia was profoundly reflective of the feudal system which, functioning under the direction of the priestly officers of the Christian Church and a variety of kings, princes and dukes acting as defenders of the Christian faith, had for centuries directed a basically agrarian European society. As a typical feudal society in which the hard-working many were commanded by the leisured aristocratic few, Virginia was founded on the secular quest for wealth and social status measured by the size of someone's landholding and the number of people working that land for the landowner: the more land owned and the more servants working the land, the higher the social status of the landowner. Thus it was also that slavery replaced indenture as the foundation of the working-class system holding the Virginian social order together. Thus it was also that certain individuals influenced deeply the development of Virginia – such as the aristocratic Englishman Sir William Berkeley, who was undoubtedly the most important of the Virginia governors ... or Virginia colonials themselves who represented the very heart of the Virginia character – such as in the early 1700s, William Byrd with his plantation of 180,000 acres and hundreds of slaves.

All of this was considered "Christian" because the understanding was that such a hierarchical system was something that God himself had ordained ... from the aristocratic few at the top of this Christian social order down to the many common laborers, even the permanently indentured (ultimately officially enslaved) workers at the bottom of this same order. The key function of the Christian Church was to morally/spiritually authorize and protect exactly this strict social order against all forces attempting to disintegrate it.

Protestant-reformist New England. On the other hand, New England was deeply reflective of the rising urban-industrial society that had been emerging along Europe's Mediterranean, Atlantic and Baltic coastlines ... whose ambitious commercial/industrial spirit posed a profound challenge to Europe’s older rural feudal system. Largely siding with the Protestant religious reformers in the internal battle raging in Europe in the early 1600s, the New England colonists had decided to relocate to America, profoundly motivated by a deep religious quest for the right to live as God directed – not as man, not even kings or bishops, directed.

This all started with the plantation (1620s) of the Separatists (the Pilgrims) at Plymouth and then soon thereafter (1630) the migration to America led by America's first Founding Father John Winthrop, who established the settlement in the Boston area of a huge Puritan settlement (ultimately some 20,000 English over the next dozen years).

This all started with the plantation (1620s) of the Separatists (the Pilgrims) at Plymouth and then soon thereafter (1630) the migration to America led by America's first Founding Father John Winthrop, who established the settlement in the Boston area of a huge Puritan settlement (ultimately some 20,000 English over the next dozen years).

In John Winthrop's famous "City on a Hill" sermon (actually entitled by Winthrop himself as "A Modell of Christian Charity.") Winthrop explained to the English settlers, who were about to embark to the New World, how this covenant – on which their new settlement was to be based – actually worked. He detailed both the good that would come from observing the exact terms of the covenant ... and the bad that would result if the covenant was not followed by the settlers – social rules derived from the example of ancient Israel ... and its wanderings. Now it was the Puritans' opportunity in Massachusetts to be a "New Israel" – a "Light to the Nations" ... a very visible example to the world of how God expected human life to operate.

In line with Winthrop's vision, the new arrivals were carefully placed in numerous villages in the region, everyone receiving roughly equal property allotments in order to emphasize the basic equality of all in New England, because they were most importantly equal before the Lord. Indeed, this was done purposefully in order to create a "Light to the Nations" which would show others the way to this same egalitarian or "democratic" existence, mandated and supported by none other than God himself.

Thus the key distinguishing features of this new social order were 1) the deep sense of equality of all members of society, 2) the responsibility of all in assuming the toil (hard work) in God’s vineyard necessary to make this Godly society succeed, and 3) that those who took the responsibility to guide this society (its religious and civil officers) were servants – not owners – of this society, regularly elected to office by its members – and recalled by them if need be – and did not constitute some permanently privileged social group.

Politics. Being so new, this grand social experiment of course would draw opinions even from the settlers themselves as to how all of this was supposed to work. In a few cases (detailed in this study) voices of dissent arose from especially active egos, some quite disruptive of the quite fragile social harmony (those of Roger Williams and Anne Hutchinson, for instance) which ultimately led to their invitation to go elsewhere before they collapsed the colony's social order. Others such as Connecticut's Thomas Hooker, however, left of his own desire to go a different way socially and politically – yet did so with the blessings of the Boston authorities. And anyway, in the end, Winthrop, Williams and Hooker found that working closely together nonetheless was the very best strategy for them all.

Other colonies and their founders. The narrative then turns to the establishment of the other American colonies: Maryland, the Carolinas, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and finally Georgia. It pays close attention to the particular individuals who played the leading roles in the establishment of these colonies (the Carterets, Shaftesbury, James Duke of York, William Penn, James Oglethorpe, and others).

Problems in social-moral development. It then turns to the matter of how these colonies matured, especially the Puritan communities in New England, noting that it did not take long before worldly success brought the generations that followed the original Puritan settlers (the high-risk and deeply dedicated Christian "First Generation") to be of a much less impressive character (something akin to the "Fourth Generation" as explained in the preface). Thus it was that in the 1690s, a huge panic over the intrusion of witchcraft into the life of a supposedly Christian New England turned very ugly – although the panic blew over fairly quickly.

The coming of the Human Enlightenment. But there were other problems as well. It was the Age of the Human Enlightenment (late 1600s / early 1700s). Discoveries were being made suggesting that the world operated entirely along mechanical lines (17th century Secularism), and that human rational inquiry into these mechanics would soon remove life's great mysteries and indeed bring life under full human mastery (17th century Humanism). At least that was the hope. And thus Secular-Humanism was set loose as a huge cultural-spiritual force, already challenging deeply as early as the late 1600s the traditional beliefs of Christians that the world, the universe itself even, was under God's full sovereignty.

The new powers that the Enlightenment promised the "man of reason" seemed to put that same sovereignty into man's own hands. This new worldview (religion) was powerful stuff for human egos to navigate through!

Thus churches were emptying out by the early 1700s, despite efforts of "enlightened" theologians to amend the Christian faith in order to put it more closely in line with the new doctrines of the Enlightenment. In fact the emptying of churches was greatly enhanced by exactly that effort to "update" Christianity.

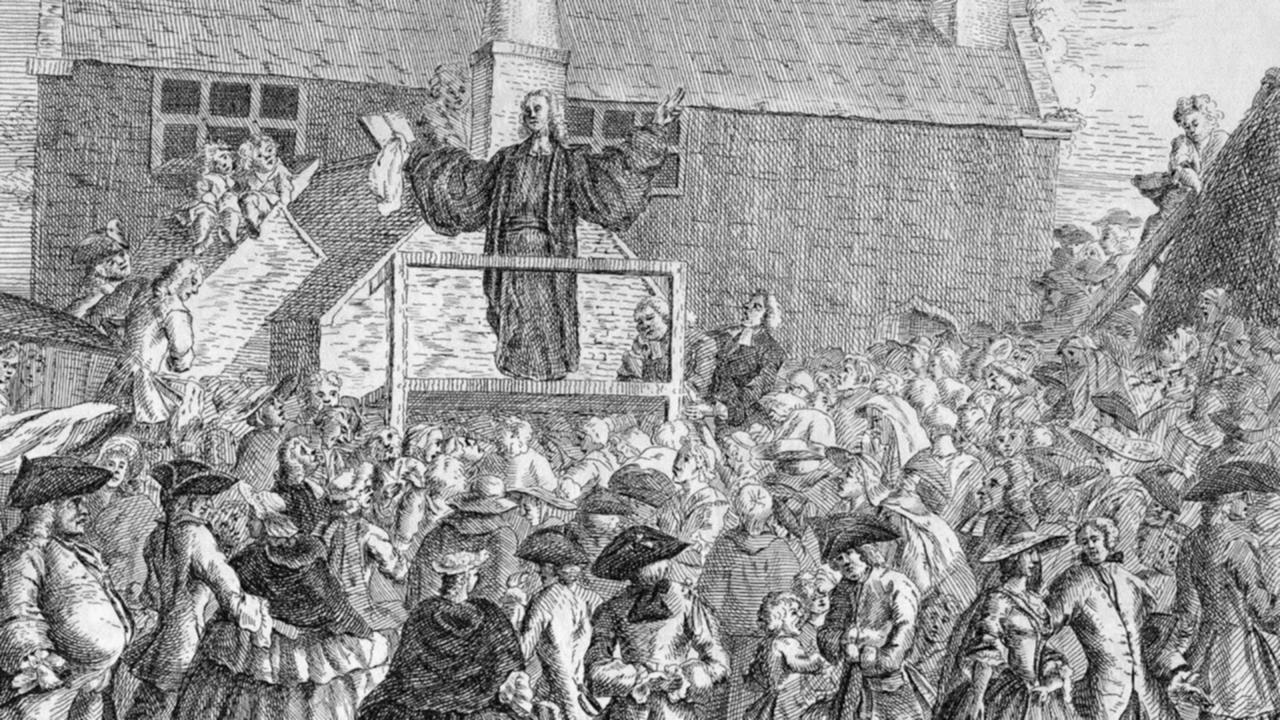

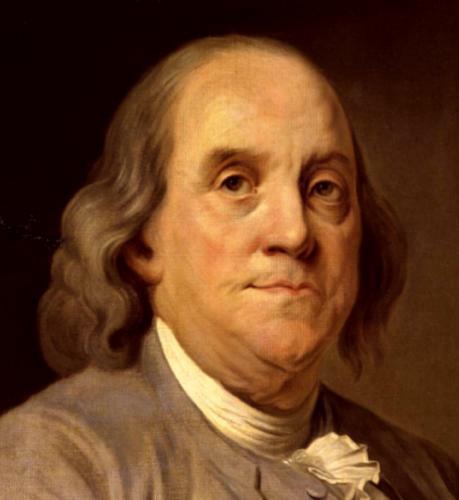

The Christian "Great Awakening." Then seemingly out of nowhere, a deep earth-shaking Christian revival began to move through the colonies, drawing huge crowds out onto the open fields and city streets (what? not properly located inside a church?), this revival gaining force as it went. Importantly, George Whitefield personally brought much of this spirit of Christian revival from England where revivalists (John Wesley and the Methodists) were involved in the same process of bringing revival to that country. But there were individuals locally (Edwards, Freylinghuisen, and many others) who were also stirring the same fires in America, first in New England and in the Middle Colonies – then eventually across the full Anglo-American spectrum, especially resulting from the dynamic energy of Whitefield. Even the "common-sense" American philosopher Ben Franklin was drawn in by Whitefield's preaching. In short, America was experiencing a "Great Awakening" – starting in the mid-1730s and running all the way into the 1760s, though the height of the movement occurred in the 1740s.

Moral strength to protect the American experiment. This was a very good thing for the American colonials, because they would need that faith in a presiding God to face the dangers that a new (1760) King of England, George III, would pose to the enormous social freedoms they enjoyed in America. The American colonials were long used to taking care of themselves – completely. And American self-rule had been merely deepened in having the two previous English kings (George I and II) of the early and mid-1700s not only unable to speak English (they were actually German) but preferring to spend their times focused on European, not American, affairs – when not out also hunting and sporting. But George II's grandson, George III, intended to correct this negligence of his predecessors. Troubles thus brewed for the colonies.

In the mid-1770s the explosion finally occurred in the colonies when George III tried to break this American spirit with heavy taxation, the posting of his soldiers in private homes, and the shutting down of Boston when that city refused to bend to his will. But to rise up against a sitting King was unprecedented – at least unprecedented in actually succeeding in such an endeavor. Indeed, should the rebels, who now gathered in New England in full rebellion, fail in that rebellion (as was historically always the case) they would all be put to death for their treason. Such rebellion was an incredibly brave thing for these colonial Patriots (or "Whigs") to undertake. So dangerous was such an enterprise that actually only about 40% of the population actively supported the rebellion. About 30% supported the King (thus labeled Loyalists or "Tories") and the rest were merely neutral, most of them going with whichever side seemed to be in the lead at the moment.

In the mid-1770s the explosion finally occurred in the colonies when George III tried to break this American spirit with heavy taxation, the posting of his soldiers in private homes, and the shutting down of Boston when that city refused to bend to his will. But to rise up against a sitting King was unprecedented – at least unprecedented in actually succeeding in such an endeavor. Indeed, should the rebels, who now gathered in New England in full rebellion, fail in that rebellion (as was historically always the case) they would all be put to death for their treason. Such rebellion was an incredibly brave thing for these colonial Patriots (or "Whigs") to undertake. So dangerous was such an enterprise that actually only about 40% of the population actively supported the rebellion. About 30% supported the King (thus labeled Loyalists or "Tories") and the rest were merely neutral, most of them going with whichever side seemed to be in the lead at the moment.

Washington's all-critical leadership. But the Patriots were led by the Virginian, George Washington, whose close reliance on God and not fellow man (many of whom among the other American commanding officers were a constant problem) made him the leader he was, able to keep going through the darkest of days – and keep his men staying with him in the process. Such persistence caused the English finally to tire of this game (1783), especially after the humiliating British defeat at Yorktown by the American troops led by Washington and his ever-faithful Alexander Hamilton ... and also with the major contribution of America's French allies (led by Lafayette and Admiral de Grasse).

Basing the Constitution on American tradition – and God's support (1787). But the same bold spirit was found elsewhere among many of America's leaders who after the war gathered in Philadelphia to put together a Constitution defining a new political union among the thirteen newly independent states. But they were having trouble in peacetime finding the pressure to continue to "reason together" – and had to be reminded by Franklin that instead of arguing constantly over their "reasonable" but unresolvable differences (as lawyers are skilled at doing) they should remember how they got through the recent war with Britain when they went before God for help. So he invited the group to go daily before the Lord in prayer for guidance, a much better guidance than merely trying to build their new society on human reason (which clearly wasn't working at that point)!

Basing the Constitution on American tradition – and God's support (1787). But the same bold spirit was found elsewhere among many of America's leaders who after the war gathered in Philadelphia to put together a Constitution defining a new political union among the thirteen newly independent states. But they were having trouble in peacetime finding the pressure to continue to "reason together" – and had to be reminded by Franklin that instead of arguing constantly over their "reasonable" but unresolvable differences (as lawyers are skilled at doing) they should remember how they got through the recent war with Britain when they went before God for help. So he invited the group to go daily before the Lord in prayer for guidance, a much better guidance than merely trying to build their new society on human reason (which clearly wasn't working at that point)!

It is important to note why this author does not follow the general trend of referring to this war they had just gone through as the "Revolutionary War" – but instead always refers to it as the "War of Independence." America itself did not change in character. In that all-important way America itself underwent no "revolution." It simply fought to preserve the very political and social character that had been long-established in America, a political-social quality that Americans refused to give up to George III. Certainly independence was achieved in this very bloody struggle. But nothing "revolutionary" happened to the way America went about its usual social business, either before or after the war!

For instance, the Americans did not newly invent Constitutional government ... all the colonies having been run according to very precise legal principles outlined in their founding charters laid out a century and a half earlier (but updated as the need arose). They planned to continue as independent "states" in exactly the same manner. Thus upon their move to independence in 1776, each of the colonies had worked quickly to draft up new charters or state constitutions. In short, such self-government was by no means a "revolutionary" development for Americans. They were well-practiced in self-government according to well-established legal principles.

The wisdom of the "Framers" of the Constitution. Anyway, after a long hot summer, the Constitutional "Framers" finally put the finishing touches on their political union, drawn up as a contract, providing for a new Congress, a President, and a Supreme Court to guide the Union ... in a tightly defined and tightly restricted realm of political operation (mostly in the area of foreign affairs, where these thirteen new states were indeed weakest in their operations).

Also a Bill of Rights was passed in accompaniment to the new Constitution, guaranteeing that the new Union government would not ever be able to accumulate powers (as power tends to want to do by its very nature) so that America would end up being governed no longer by the states and their people but instead by an autocratic authority that attempted to dominate American life the way King George had tried to do.

But just as history (including their own) had so clearly revealed to those gentlemen who put this new government together, they could have never succeeded in getting to this point (in other words, freed from royal tyranny) if God had not been with them. By the same token, there was also little likelihood that they would be able to keep their personal freedoms from any government they might have set up if it too did not ultimately remain under the supervision of God Almighty.

History revealed no example of any political system that ultimately did not fall into some form of human tyranny – because of the very nature of power-hungry man himself ... and his well-developed ability to rationalize legally and morally his accumulation of ever-widening personal and social power.

And thus when Franklin was questioned upon the completion of the work of the Constitutional Convention as to what exact form of government these gentlemen had come up with, he replied, "A Republic ... if you can keep it."

Again, without God (not man) as the ultimate guarantor of the integrity of this political experiment, these wise ones who put that Constitution together knew quite well that their new Republic would not last long before it too fell into the hands of the Enlightened Ones – in the same way that the "enlightened" despots of Europe (the various European kings) stepped forward during the height of the so-called Human Enlightenment to justify their absolute power over their subject peoples.

Human Enlightenment and human tyranny seemed so easily to go hand-in-hand.

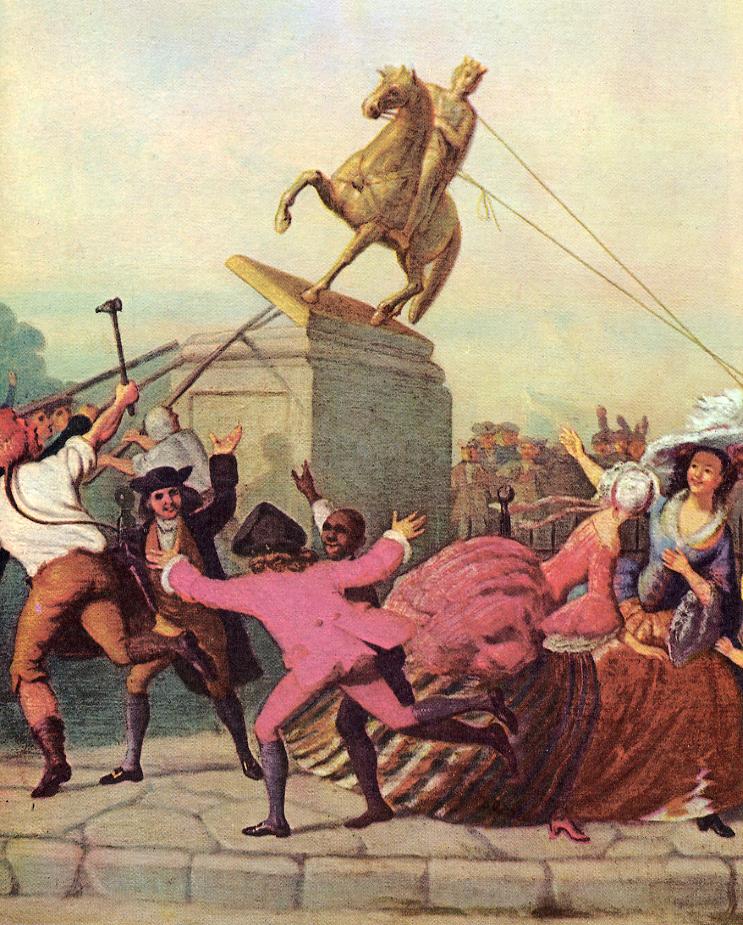

The French Revolution by way of contrast. Tragically, the same year that the American Constitution received the requisite number of state ratifications, thus taking full effect (1789), a horrible Revolution broke out in France – and was truly a Revolution ... because the enlightened ones directing its course intended to "change" everything possible about the very character of French society.

But disaster merely resulted because, unlike the Framers of the American constitution, the leaders of the French Revolution had only bright ideas – and no practical or deeply tested experience in guiding and directing a society. Nor did the French people themselves have any understanding of what their role was to be in this new Revolutionary society.

Very quickly the Revolution collapsed into a murderous chaos, with not only the ruling class of the Ancien Régime (France's king and queen, its barons and aristocrats, its bishops and clergy, etc.) being beheaded at the guillotine – but then also (especially during the years 1793-1794, a period known today as the French "Reign of Terror") the "enlightened ones" themselves. The leading revolutionary groups, the Girondins and Jacobins, savagely turned on each other over points of differences in their "pure" thinking! It finally took the military-based dictatorship of Napoleon to put France back together again!

How very different the American and French political dynamics proved to be. Human Reason had no known well-established moral restraints functioning in France at this point, moral restraints necessary to keep such "enlightenment" from the typically self-destructive behavior that results when human egos find clever ways to justify their insatiable quest for power.

On the other hand, America's leaders were well aware of the dangers of trusting to merely self-justifying Human Reason to direct them. They were quite aware that God – whose rules for human behavior were as eternal as the laws of physics and chemistry – had to stay sovereign over these United States, or they too would drift down the "creative" or "progressive" path of Human Reason that the French Revolutionaries had foolishly followed.

Washington's presidency (1789-1797). Everyone knew all along who the union's first president was supposed to be. Washington accepted the responsibility, certainly preferring instead to go home to his Mount Vernon home. But duty called, and he cautiously said yes.

He formed a cabinet to support his office, appointing Hamilton to head Treasury and Jefferson to head his foreign office as Secretary of State. Hamilton faced the enormous challenge of putting the government's credit rating (based on the reputation of its dollar currency) back on firm footing, which at the time was a total disaster. And Jefferson was faced with the issue of the American response to the on-going war between France and Britain that America was having a very hard time keeping it away from its door.

In meeting these challenges, Hamilton was highly successful – and Jefferson was not. Hamilton took up very unpopular, but very necessary, actions to strengthen America's financial foundations (key to any nation's power). But Jefferson was so enamored with things French that he found himself lined up against Hamilton who understood that the British served American interests at the time much better than France – and that the forces driving France were destined ultimately to lead that country to ruin ... which Jefferson could not (or just would not) see coming. And Washington agreed with Hamilton, infuriating Jefferson. Jefferson thus resigned in anger from the cabinet (1793) ... and then had his friend Madison also pull back as a Federalist and become an anti-Federalist (like Jefferson) – and in fact form a new political party that would oppose the Federalists (importantly Washington and Hamilton) by whatever means available. Thus America's two-party system got off and running!

People barely got Washington to accept a second 4-year term as President. And when that term was up, Washington refused to serve further. He was fed up with all the political back-stabbing going on at the time (welcome, Mr. Washington, to the world of politics!)

Thus in so many ways Washington personally put the final touches on how the American presidency was to take shape – including the rule that a president should serve no more than two terms (which Franklin Roosevelt later ignored, thus forcing the adoption of the 22nd Amendment in 1951).

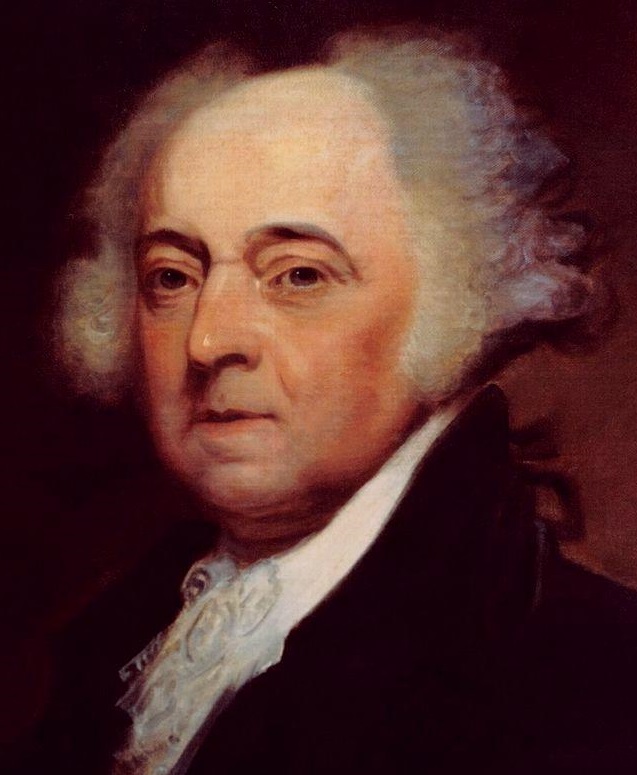

John Adams. John Adams then stepped up as president. The French-British turmoil constantly troubled his presidency, ultimately destining him to a single term when he refused to follow the impulse of his fellow Federalists, who wanted him to declare war against France, which would have been disastrous for America – a very brave act on Adams's part.

John Adams. John Adams then stepped up as president. The French-British turmoil constantly troubled his presidency, ultimately destining him to a single term when he refused to follow the impulse of his fellow Federalists, who wanted him to declare war against France, which would have been disastrous for America – a very brave act on Adams's part.

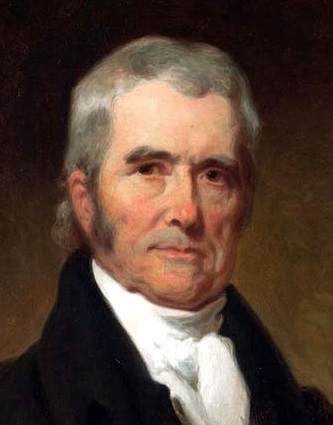

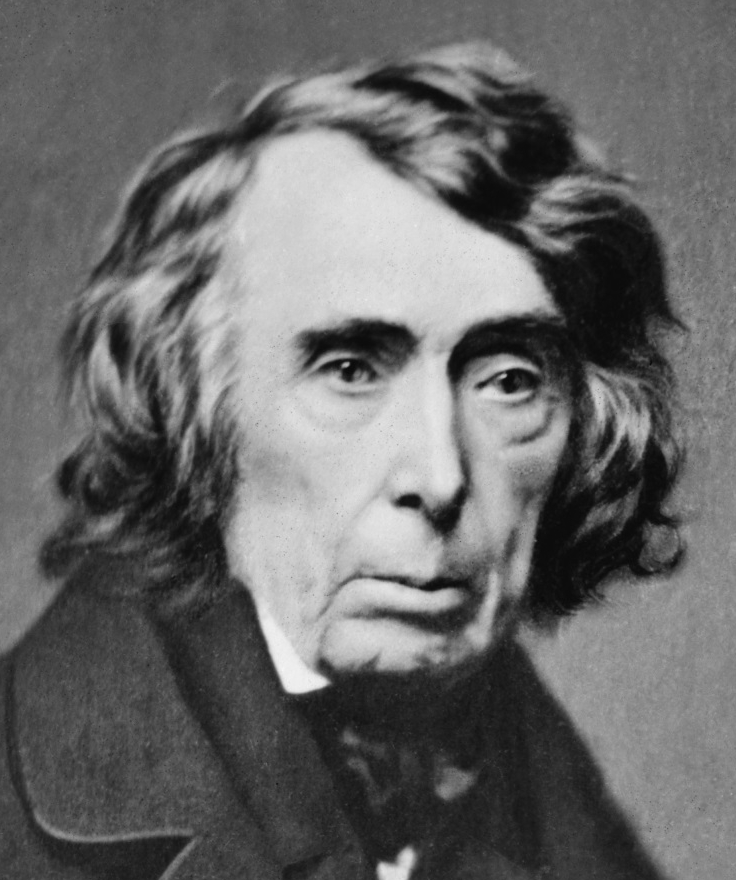

John Marshall's Supreme Court. But Adams did something that would have a huge impact on the way the young Republic would go forward constitutionally ... when in his last days in office he appointed John Marshall to the position of Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Although he was a Virginian, Marshall did not follow the other Virginians into Jefferson's political camp, but remained a resolved Federalist. In fact, in his 34 years of Supreme Court service (1801-1835), he turned this panel of judges into something more akin to true legislators, revising the law of the land at will. Not only did his court pass judgment on legal contests that inevitably arise from applying the law in particular cases (the traditional role of English judges) ... he actually went well beyond that in deciding how such laws should be interpreted or even be reinterpreted ... or even be set aside as "unconstitutional" – according to his own personal Federalist political instincts. But these could be almost anything he deemed as "reasonable." Thus slowly he was reshaping Constitutional Law so as to make it conform to the logic or reason of a small group of jurists who happened to be sitting on the bench – actually only a simple majority among them being required for a wide-sweeping decision.

John Marshall's Supreme Court. But Adams did something that would have a huge impact on the way the young Republic would go forward constitutionally ... when in his last days in office he appointed John Marshall to the position of Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Although he was a Virginian, Marshall did not follow the other Virginians into Jefferson's political camp, but remained a resolved Federalist. In fact, in his 34 years of Supreme Court service (1801-1835), he turned this panel of judges into something more akin to true legislators, revising the law of the land at will. Not only did his court pass judgment on legal contests that inevitably arise from applying the law in particular cases (the traditional role of English judges) ... he actually went well beyond that in deciding how such laws should be interpreted or even be reinterpreted ... or even be set aside as "unconstitutional" – according to his own personal Federalist political instincts. But these could be almost anything he deemed as "reasonable." Thus slowly he was reshaping Constitutional Law so as to make it conform to the logic or reason of a small group of jurists who happened to be sitting on the bench – actually only a simple majority among them being required for a wide-sweeping decision.

And there was no built-in "check" on such enormous power. Justices, once appointed, served for life – not subject to any subsequent elections or renewals of their appointments by the world other than their deaths (or voluntary retirement) itself. Tragically, the Framers of the Constitution did not see this power-expansion coming. No such power as the Supreme Court assumed for itself was actually ever assigned by the Constitution. And the English political tradition that the Framers thought they were working with had no such grants of political power assigned to their judges. This political expansion was all a result of Marshall's personal creativity.

Wow! Lawyers in black robes! But what else did anyone think was likely to occur if nothing was said or noticed at the time.

In any case, this single judicial appointment would establish a political path that would slowly make the Supreme Court, not Congress, the supreme legislative body of the land.

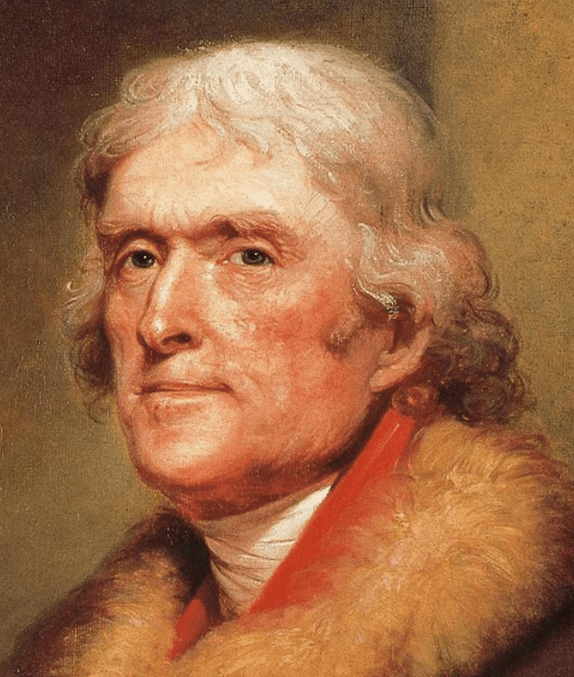

Jefferson's presidency (1801-1809). Jefferson and his Republican Party (no connection with the modern Republican Party) now had a chance to shift the political dynamic away from the growing industrial-financial power of Hamilton's Federalists (located heavily in coastal New England and the central states) and move power in favor of the Southerners and also the Western farmers and frontiersmen.

Jefferson's presidency (1801-1809). Jefferson and his Republican Party (no connection with the modern Republican Party) now had a chance to shift the political dynamic away from the growing industrial-financial power of Hamilton's Federalists (located heavily in coastal New England and the central states) and move power in favor of the Southerners and also the Western farmers and frontiersmen.

Jefferson was a hard figure to pin down because he lived so much in the world of his own making. He got the bright idea to reduce the size of the U.S. military and navy – yet at the same time ordered a fairly successful naval and land attack on the Barbary pirates of North Africa, who had been harassing American shipping and kidnapping American sailors (for ransom payments or slavery).

And he did initiate what would turn out in 1803 to double the land size of America when his agents in France agreed to purchase not only the strategic city of New Orleans (their original plan was to purchase that site for up to $10 million) but for a mere $5 million more the entire Louisiana region of the American West. Ironically it was Hamilton's tough financial policies, the very ones that Jefferson had hated so much, that gave the American dollar the creditworthiness needed to make this purchase feasible in the first place!

But Jefferson also most arrogantly (and stupidly) decided that the way to defend the American nation in the all-consuming British-French struggle (the Brits were grabbing American sailors from American ships and dragging them into British naval service) was to block American shipping to Britain, convinced that this loss of American input would bring Britain to its knees in repentance. But instead it simply gave the appearance to the British that America was aligning itself with France in Napoleon's similar effort to blockade Britain and bring its economy to defeat. Thus the British responded in ever-greater fury, not repentance. Then to make things "fairer," Jefferson decided to extend the same restriction against trade with France as well, shutting down pretty much all of America's export business – and nearly collapsing the American economy.

For one who had been so loud about protecting "states' rights" against the assumption of autocratic power by an uncontrolled government in Washington, Jefferson had no problems personally acting in such an autocratic fashion when he himself was president. But of course he was among the most "enlightened" of Americans, and that justified his autocracy (as "enlightenment" always does!).

Finally in his last days in office, he lifted his restrictions ... and the American economy began to recover.

The War of 1812 (actually 1812-1815). When Jefferson's understudy Madison stepped up to be president, American politics was beginning to make another shift. A younger generation of Republicans had come into Jefferson's party, much more nationalistic (thus less "states rightist") in temperament than Jefferson's traditionally Virginia gentlemen-led organization. In fact, John Adams's son, John Quincy Adams would join the new Republicans – an indicator of how badly the Federalists were losing political support among the rising generation of Americans.

The War of 1812 (actually 1812-1815). When Jefferson's understudy Madison stepped up to be president, American politics was beginning to make another shift. A younger generation of Republicans had come into Jefferson's party, much more nationalistic (thus less "states rightist") in temperament than Jefferson's traditionally Virginia gentlemen-led organization. In fact, John Adams's son, John Quincy Adams would join the new Republicans – an indicator of how badly the Federalists were losing political support among the rising generation of Americans.

But a big part of this changing political dynamic was the growing question of how the battle between France and Britain impacted the political alignment of Americans. The American national spirit was coming alive, outpacing American loyalties to Massachusetts, New York, Virginia, etc.

A big part of this growing nationalist mood was the treatment that America was still receiving at the hands of the European powers, most notably Britain – driving the Americans to such anger that finally in 1812 they declared war on Britain. With not much of a navy (thanks to Jefferson) and really only state militias to work with, this was not a good time to be taking on the mighty British Empire. In fact things did not initially go all that well for America. Americans did succeed in burning down the Canadian capital at York (Toronto) – but would pay for that when the British did the same to Washington, D.C.

But America got some help with a naval victory on the Great Lakes and the failure of the British to move further inland into America when they found themselves unable to get past the American defenses at Baltimore (giving America its national anthem: The Star-Spangled Banner). Besides, Napoleon was (apparently) defeated by that time (late 1814), and anyway the British were tired of all the fighting that had been going on for so long. America and Britain thus signed a treaty in Belgium, pretty much recognizing the status quo prior to the war. Thus the war was officially over.

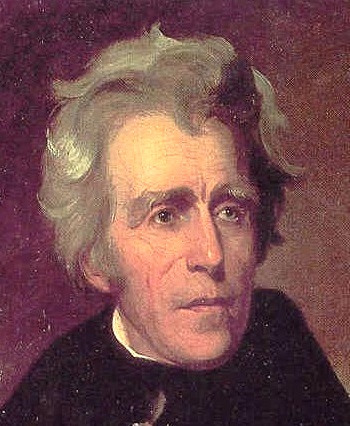

But the news did not reach America before General Andrew Jackson's men made a stand at New Orleans against a huge British assault there – in which the British were absolutely devastated!

Ultimately it made no difference in terms of the peace agreement. But it definitely gave America a new hero to worship and adore: Jackson himself!

The James Monroe / John Quincy Adams presidencies. Nothing quite as dramatic as the previous presidencies would characterize the presidencies of the next two individuals in their 12 years in the White House. One journalist termed the time period the "Era of Good Feelings" ... although a deep post-war recession set in upon America when the Europeans got out of their uniforms and back into their work clothes. The demand for American goods dropped dramatically after the war, hurting the American economy deeply. Likewise, the arrival on the world market of cotton from India at about this same time did not help the Southern economy either.

But in the field of foreign affairs, things worked much more smoothly for the young republic. America put its relations with Britain back in good order. It was even able to be so bold as to threaten Spain, France or any European power to keep its hands off its newly-independent neighbors to the South – because Monroe, in announcing his famous "Monroe Doctrine" knew that he had the interests of the British navy behind him in making that threat. The British wanted these new countries to remain open to "free trade" (that is, British trade) which had been impossible as long as the Spanish had been controlling those areas as colonies of their own ("mercantilism").

But that did not keep the Americans from helping themselves to Spanish territory, when in 1817 war hero Jackson was ordered to do something to stop the raids from Spanish Florida into Georgia by the Seminole Indians – and Jackson simply invaded Florida, crushed the Seminoles ... and embarrassed the Spanish into simply agreeing to sell Florida to America for $5 million. This was not something that Monroe had called for. But it so stoked the fires of American nationalism that Monroe had to go along with the deal.

Likewise, politics abroad were in such a calm state during the younger Adams's presidency that nothing remarkable occurred during his four years in office (partly due to the fact that Adams himself had been Monroe's Secretary of State and had conducted a strong but quiet diplomacy.

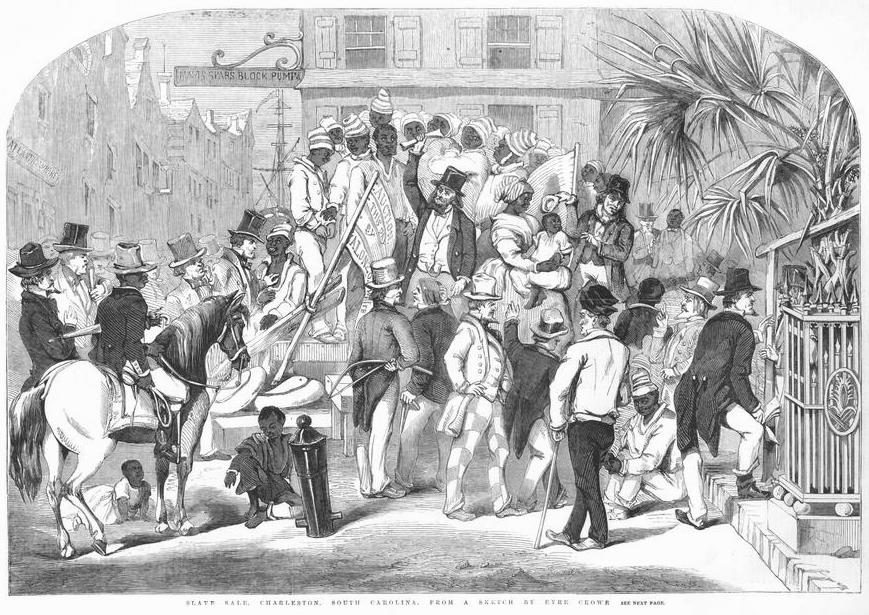

Slavery. But there was an issue troubling deeply the domestic politics of America: slavery. By the early 1800s, America had arrived at the point where its two very different social-moral systems were contesting each other for the heart of the nation.

It is very hard for a society based strongly on a particular worldview to understand the logic or reasoning of another society working from a different worldview. They can discuss or "reason" with each other until a point of exhaustion. But they are never going to come to an agreement on key social-moral issues, because they are operating from such different perspectives, from such different "basic truths."

And the holding of humans in a state of slavery would be one of those issues that would divide America into two cultural warring camps.

Slavery had been around for a very long time. For instance, the Apostle Paul in the first century AD addressed slaves in the Christian social circle along with Christian free citizens in his advice as to how the Christian life should be lived out.

Slavery certainly also existed in the North in the early 1800s, although rather marginally, and eventually only with some apology. When the Northwest Territories (Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, Michigan and portions of Minnesota) were set up in 1787, slavery was entirely forbidden in those future states. But that's as far as things went legally in America at the time. Elsewhere Americans were allowed to practice slavery without legal restriction – although morally speaking, it got a fair amount of resistance in the other Northern States.

But in the American South it was not only practiced, it was increasingly glorified as the very Godly thing to do, because God himself had commanded the African to be forever the servant of the White man. And step by step such moral reasoning or justification merely dug deeper into Southern thinking and social-moral structuring – as Southerners reacted to the challenges of Northern voices (the "Abolitionists") calling for the end to such human bondage.

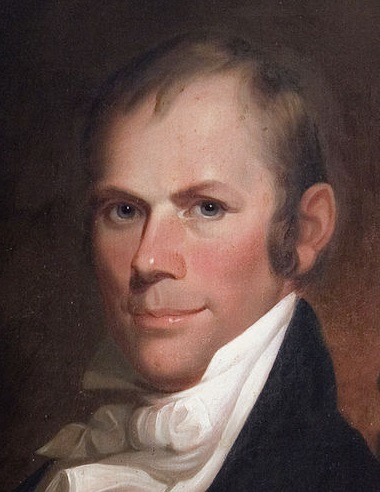

The Missouri Compromise of 1820. In 1820 the issue came to the fore when the Missouri territory requested entrance into the Union as one of its new states. At this point there was an even divide between the eleven Northern "free" states and the eleven Southern "slave" states making up the Union. Thus automatically the question arose as to where Missouri was to fall in the matter of this divide. Slavery was long-practiced in the state and thus Missouri was certainly going to enter the Union as a slave state, tipping the balance in favor of the pro-slavery position, unless it became a free state by releasing all of its slaves from bondage. But there was little likelihood of that happening. Not only was a lot of wealth to be lost by slave owners in doing so, there was even more importantly the matter of principle. If slavery needed to be ended in Missouri, what then was keeping radical anti-slavery voices (however, not that numerous at the time) from demanding the same of the Southern states? Tempers flared.

Finally "the Great Compromiser" Henry Clay stepped forward to offer a solution: a compromise on the matter (especially since Maine, a free state, was also seeking entry into the Union at the same time): a line running across the young nation west of the Mississippi River (basically an extension of the Mason-Dixon Line) would be drawn with the understanding that all states and territories south of that line would automatically be eligible to enter the Union as slave states while north of it all would have to be "free-soil" states – with the exception of Missouri, which lay north of that line. It would be permitted to enter the Union as a slave state.

Finally "the Great Compromiser" Henry Clay stepped forward to offer a solution: a compromise on the matter (especially since Maine, a free state, was also seeking entry into the Union at the same time): a line running across the young nation west of the Mississippi River (basically an extension of the Mason-Dixon Line) would be drawn with the understanding that all states and territories south of that line would automatically be eligible to enter the Union as slave states while north of it all would have to be "free-soil" states – with the exception of Missouri, which lay north of that line. It would be permitted to enter the Union as a slave state.

This seemed like a reasonable solution to a complex problem. Thus supposedly Clay had saved the nation from calamity through his famous "Missouri Compromise." Actually, nothing of the sort had taken place. In fact the whole issue merely clarified, and thus deepened, the North-South division over the matter of slavery. America was taking its first steps in becoming not one but two distinct nations. This did not bode well for the Union.

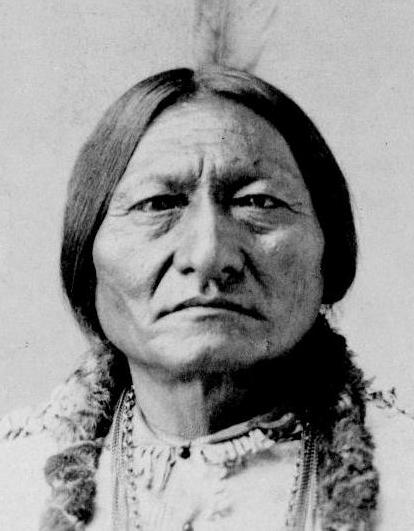

The growing "Indian Problem." Then there was this other matter confronting America at that time, one that continues even today to stir controversy. Of course the context today is very different than the one two centuries ago when Anglo relations with the Indians were problematic in a very material (life and death) way.

From the very arrival of the Anglos to the shores of America in the early 1600s, relations with the Indians would be problematic. The Anglos saw only forests and uncultivated land before them. In other words, the land itself was "unoccupied." There were Indians who hunted those woodlands, of course. But to the Anglos this did not make them "property owners" – in the way that the Anglos understood proprietorship. Some of the Anglos (Williams and Penn for instance) struck deals to purchase property rights from neighboring Indian tribes. This helped make the contest with the Indians for the land a bit more manageable. But for neither party did that provide any kind of permanent solution.

Ultimately the Anglo-Indian matter came to be simply that of which of them was going to get to occupy the land, for whatever legitimate purposes (hunting or farming) and by whatever rights each understood their land claims to be based on.

To the Indians there was nothing new about this problem. The Indians had been fighting each other, tribe against tribe, since time immemorial. And there was no compromise in such struggle. A tribe had control of certain territory – or it did not. And on that matter tribal life depended completely. Thus Indians were by all necessity warriors – warriors who either won in battle or were simply exterminated. Some slavery did exist among the Indians. But in general the Indians had no use for defeated enemies. They could not, and certainly would not, feed or otherwise support a defeated enemy. The woodlands could support only so many people. And that's why they fought in the first place.

Then along came multitudes of Anglos, anxious to place their families on that same land. And in the Anglo-Indian contest for the land that naturally followed, here also – as was the case among the Indian tribes themselves – there was little room for compromise. Thus the Anglo-Indian wars quickly became wars whose goals became that of totally annihilating the other.

Andrew Jackson and the Indian Removal (the 1830s). The particular context of the early 1800s in which the "Indian Problem" presented itself to Anglo America at that time was that the Indians had taken the opportunity recently offered them by the American preoccupation with Britain during the war of 1812 (the Indians had even allied with the British) to take their revenge on poorly protected Anglo communities in the West. The slaughter was terrible – producing in turn a desire for revenge among the Anglos.

Then when the American governor of the state of Georgia – exercising "states' rights" because he had seen little action on the part of Washington – declared that the numerous Indian tribes living within Georgia were going to have to leave his state and reposition themselves west of the Mississippi River in the "Indian Territory" of Oklahoma, the Cherokee Tribe resisted the order by going to Marshall's Supreme Court to fight that order. The Cherokee had tried to "fit in." But Georgian authorities would have none of that.

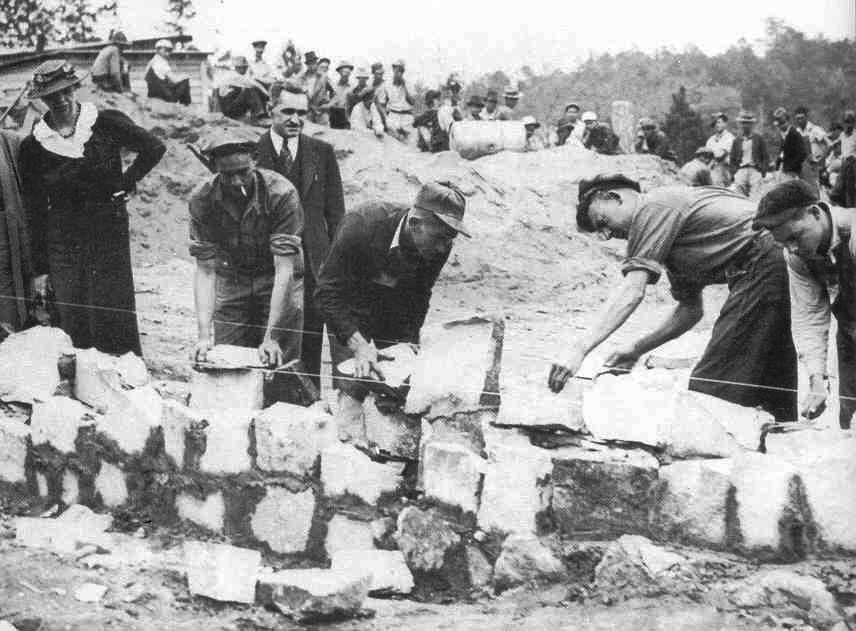

And that brings us to Jackson, hero of New Orleans, but also hero of the crushing of the Floridian Seminoles. Now serving as U.S. president, Jackson took this opportunity as the presumed "champion of the little people" to respond to the Georgia challenge by pushing through Congress in 1830 the Indian Removal Act – not only authorizing the Georgia removal but aiming even more broadly at the entire Indian world east of the Mississippi.

And that brings us to Jackson, hero of New Orleans, but also hero of the crushing of the Floridian Seminoles. Now serving as U.S. president, Jackson took this opportunity as the presumed "champion of the little people" to respond to the Georgia challenge by pushing through Congress in 1830 the Indian Removal Act – not only authorizing the Georgia removal but aiming even more broadly at the entire Indian world east of the Mississippi.

When Supreme Court Chief Justice Marshall seemed to block such Indian removal, Jackson responded by challenging Marshall to enforce his ruling himself – since Jackson had no intentions of doing so (possibly the only time that the authority of the Supreme Court has been seriously challenged).

In any case the removal went forward over the stretch of the 1830s, the Choctaw, Seminole, Creek, Chickasaw, and finally the Cherokee tribes (some 46,000 in all) were moved west, under horrible conditions in which thousands died in the move (thus the "Trail of Tears").

But ultimately this spoke volumes as to where the Anglo-Indian matter was headed. America was to be a society based purely on Anglo culture – not some kind of ethnic-cultural blend, such as was the case for instance with Hispanic America (where very few Spanish had actually moved to the New World, thus forcing Spanish society in America to be built on an Hispanic-Indian blend).

But this left the question still standing: which Anglo or American culture? Was it the one of the rapidly industrializing world back east? Or was it the world of the Mid-Western farmers and frontiersmen? Or was it the aristocratic slave-based Southern culture that America could claim itself to be best based on? These were all very different societies, with very different interpretations of what each considered to be "proper" Christian social-moral foundations. Which one would dominate? And how would the other American societies respond to such domination?

The Second Great Awakening. But God understood clearly this cultural challenge facing the young Republic and sent into all this social "Reasoning" (basically just self-justification) a deep spiritual impulse – not quite like the First Great Awakening of the mid-1700s, but one nevertheless that would give America some guidance in answering the question: which America?

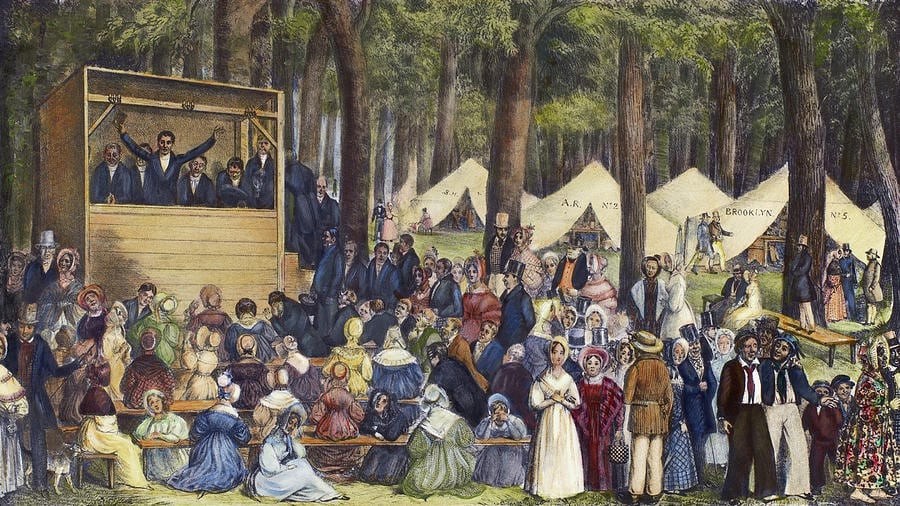

The sheer variety in the way this new Awakening produced a large number of new spiritual movements was amazing. It started here and there, particularly on the American frontier where as early as the 1790s and lasting into the 1810s Methodist leader Francis Asbury preached a total of 16,000 sermons and traveled over 275,000 miles to reach the isolated frontiersmen with the power of the Christian gospel – and building up a huge corps of Methodist frontier "circuit riders" in the process. Then there was the unusual Presbyterian revivalist, Charles Grandison Finney, who turned revival into something of a "science" with his well-organized meetings in upstate New York and New York City, which themselves became something of a model for other Christian revivalists. Then there was the area of up-state New York where the fires of revival burned so brightly that Finney himself termed it the "burned-over-district!" Here the Mormons started up under Joseph Smith, the Seventh-Day Adventists ultimately would come into being through William Miller's millennialism (expecting the coming of Christ at any time now), and the Oneida and Shaker movements were founded – all birthed in the same burned-over-district!

But there was more. This revival impulse registered itself as a strong interest in the various Christian denominations to work together in such projects as overseas mission work (the Board of Foreign Missions), the wide distribution of Bibles to the public (the American Bible Society), and ensuring that all children got to learn the stories of the Bible (the American Sunday School Union). And the denominations became very busy in founding new colleges where Christian education could be taken even more deeply into American social thinking. Thus it was that by the mid-1800s, over 500 American colleges had been founded by Christian organizations.

And in the process not only did the Christian faith warm the lonely or frightened hearts of the frontier, it moved to deepen that faith in the much more established portions of American society. Ultimately, this would again put the idea of America and its service to the world at a loftier level – reminding America that it had been founded as a "Light to the Nations," whether urban or rural, Southern or Northern ... and also Black or White. The Blacks too in the early 1800s had started up their own denominational development with the founding of the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church, and its cousin, the AME-Zion church.

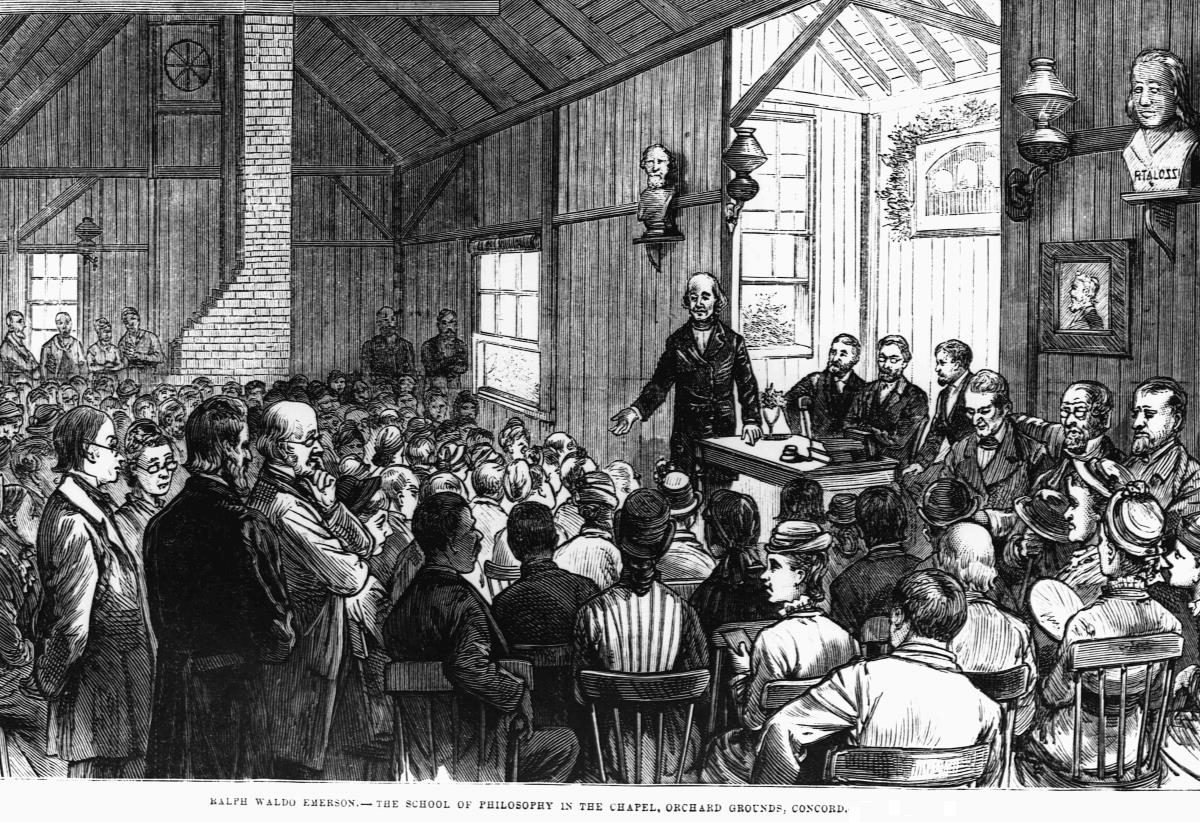

Ongoing Rationalism. Of course there were those who still clung to the faith in human reason as the more enlightened approach to life – particularly in the face of all this Christian revival. Even some of the denominations themselves once again (similar to the First Great Awakening) found members of the "Old School" distancing themselves from all the enthusiasm (meaning literally "infused with God") of the "New School" – for pretty much the same reasons as the "Old Lights" had formerly opposed the "New Lights."

Added to this step back from Christianity's revivalist spirit were such groups as the Unitarians and the Transcendentalists (strong in New England), led by such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Amos Bronson Alcott (father of novelist Louisa May Alcott) – who looked for the higher connect of their souls with the surrounding world through meditation, higher thought, or just communing more closely with nature. God played no part in their spirituality, which was entirely self-developed – often by supplementing their quest with instruction in Eastern (Hindu or Buddhist) philosophy.

Indeed, exotic spirituality played big with this group. Thankfully, witchcraft did not make much of a headway with this group!

Texas Independence (1836). With Mexico's independence from Spain in 1821 there was a growing interest in Mexico City to do some development in the very northern region of the Mexican Republic, the state of Coahuila y Tejas. This huge region had few Europeans living there – mostly just hostile Comanche Indians. Thus the decision was made in 1824 to invite Europeans and Americans to move to the region – which American southerners, whose fields were playing out because cotton is such a soil-depleting crop, answered in huge numbers.

This in turn caused the Mexican authorities to block further American immigration in 1830 – which then caused the Anglos in Texas to come step by step (1832-1835) to the decision to simply back Texas out of the Mexican Republic. This naturally resulted in war, which at first did not go well for the Texans at the Alamo and at Goliad (March 1836) – but which merely steeled the will of the Texans even more. Then the very next month (April) the army of Mexican President and General Santa Anna was soundly defeated at San Jacinto (Santa Anna was even captured trying to escape) – and the Mexicans were forced to recognize (most grudgingly) Texas independence.

But what then was the Republic of Texas to do? When in 1837 the Mexicans attempted to retake their lost province, this pushed the Texans to look to full union with the United States as their best option. But there was one huge problem that kept this from being a simple transaction: Texas's slaves. Texas's application would serve merely to reignite the slavery debate which had the potential to tear the Union apart. And besides, America was going through a tough economic crisis (the Panic of 1837), thanks to some bad fiscal decisions concerning American banking that Jackson had made. And Martin Van Buren, who followed him as U.S. president, did not want the Texas issue adding to the economic mess he was having to deal with. On top of this, the Mexicans had warned that Texas's joining the Union would cause Mexico to make this a matter of war between the two countries. Thus Van Buren did what he could to stall the Texas request for admission to the Union.

But at this point the admission of Texas to the Union had become a matter of high principle to the Southern States, pushed by John C. Calhoun, who threatened to lead the Southern states out of the Union if Texas were prevented from joining the Union. Tensions thus mounted in Washington as the Texas debate merely dragged on.

The Oregon question. Just to make matters even more complicated, the British had also been moving swiftly Westward across Canada, and had great interest in spreading southward along the Pacific Ocean into territory that Americans considered to lie within their realm of control. The British claimed land south across what is today's state of Washington, with interest in going even further through the Oregon territory all the way to California – where there was talk of the British buying that territory from the Mexicans. Americans were in a fighting mood over this question – until in June of 1846 the two sides came to an agreement to simply extend the line separating Canada and America all the way west to the Pacific (a minor adjustment around Vancouver Island). This agreement thankfully had come into play at the very same time (only a month earlier in fact) that America had found itself in a state of war with its Mexican neighbor to the south.

The Mexican-American War (1846-1848). The next president after Van Buren, John Tyler (more or less "next," because Harrison had followed Van Buren – but had held the office only a month before he died of pneumonia after conducting an overly long inauguration address, and thus his Vice President Tyler stepped into the office), also held off the matter of Texas's annexation ... until his very last day in office in March of 1845, when Tyler signed the invitation extended to Texas to join the Union.

The next president, James Polk, thus had the Mexican fury to deal with. He dangled a huge payment (early 1846) in front of the Mexicans for compensation for their loss of Texas – but knew that they wanted revenge, not bribery. Then amidst its own massive political turmoil, the Mexican government declared war on the U.S. in May of that year.

European experts expected the Mexicans to thrash the poorly mobilized American army, possibly rolling the Americans back all the way to Washington. But that is not how things turned out. Quite the opposite happened, as American troops and navy ships hit Mexico from all sides. This included the Mexican holdings in California, and the territory between California and Texas, which quickly fell into American hands. And by the summer of 1847 the U.S. army was already in Mexico City. Mexican resistance would drag on a while longer ... all the way up until February of the following year (1848) when a treaty was signed between the two parties at Guadalupe Hidalgo. Indeed a payment of $15 million was made to Mexico for its loss, which included now also California as well as Texas and the lands in between (most of Arizona, Utah and Nevada, but also sections of what would eventually become New Mexico and Colorado). The war with Mexico was over. And America had proven itself again as a fighting nation, one to be taken seriously. However, there was a lot of criticism about paying Mexico such a huge sum of money for land it lost through its own military defeat. But the decision to do so was a Godsend, for it settled down the Mexican hurt and desire for revenge ... which when the American Civil War broke out only 14 years later would have found America greatly crippled in an effort to answer a serious Mexican comeback.

The Abolitionist ("abolishing" slavery) impulse was growing in the North, especially with the publishing at the beginning of the 1850s of the major best-seller, Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin. Deep shame resulted as Christian America reacted to the fact that it for so long had tolerated the deep abuse of fellow humans as slaves.

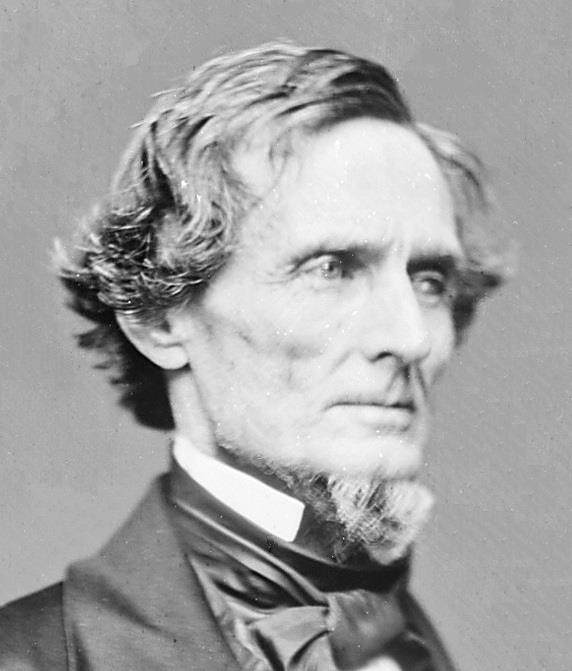

The South, of course, rather than bow to such shame, merely retreated further into social self-justification – causing any middle ground between the two sides to disappear. Besides, the great triumvirate of Henry Clay, Daniel Webster and John Calhoun, as well as John Quincy Adams (who had returned to Washington to become a leading anti-slavery voice in the Senate), all were taken from the scene by their deaths at the beginning of the 1850s. "Rational" discourse that could possibly find compromise between the two sides thus would find no voice in the halls of national power. America was headed to deep, actually violent, division.

"Bleeding Kansas." That violence showed up in the effort of the Nebraska territory to join the Union. This was a big piece of land and ultimately it was divided into two states (also helping to keep the dual balance between the Northern and Southern states): Nebraska itself, admitted easily as a "Free-Soil" state ... and Kansas. But the Kansas portion became highly problematic, having strong and opposing opinions on the matter of slavery itself held by the Kansans. It lay north of the supposed slavery dividing line and thus should have been considered "Free-Soil." But California had been admitted as a free-soil state, even though much of it fell geographically below that line. Thus the old Clay compromise North-South line no longer mattered. Then what to do about Kansas?

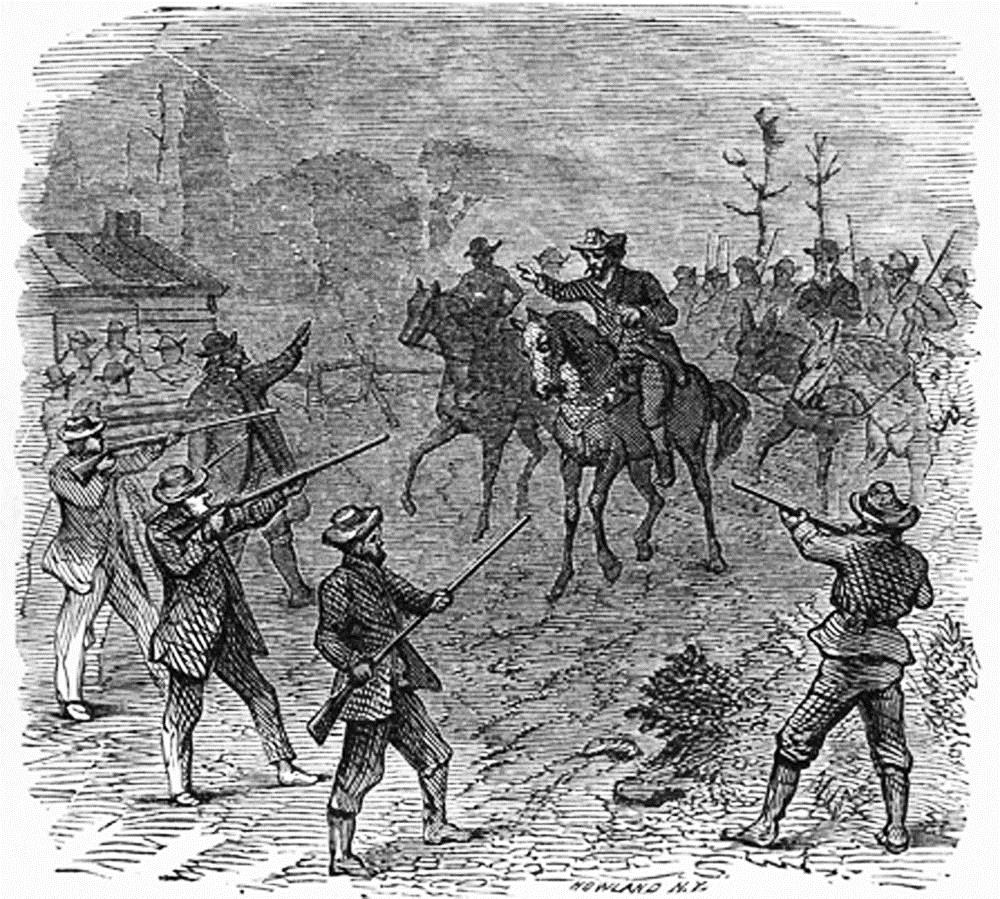

The seemingly "rational" solution was to let the Kansans decide that matter themselves (sort of a pro-South "states-rights" solution). It turned out to be the worst decision possible (as "democracy" often can be). Immediately the two sides started lining up against each other, the bitterness increasing as others poured into the northern and southern regions of Kansas to strengthen one side against the other. Then the shooting and torching of farms and towns by angry raiders (such as John Brown and his gang) of both sides turned Kansas into a nightmare of violence. In fact, by the mid-1850s, the Civil War had actually begun – at least in Kansas!

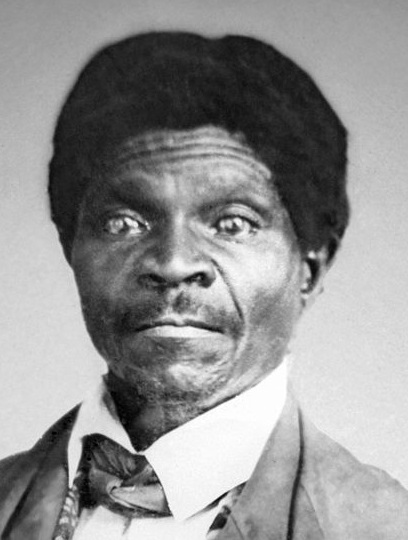

The Dred Scott Case (1857). Then there was hope that the Supreme Court could bring wisdom to the controversy when the Dred Scott case was brought before it. But in the decision announced by the court's Chief Justice Roger Taney (a Marylander with Southern views), not only was the Black slave Dred Scott's appeal for freedom denied, but Taney went on to deny that Blacks had any rights under American law, even in the North. The South was ecstatic! The Supreme Court had not only endorsed the South's institution of slavery, but implied that anti-slavery laws in the North were unconstitutional!

But Taney's ideology posing as constitutional law (not exactly unprecedented) got nowhere with the North. And besides tarnishing the reputation of the Supreme Court, the decision merely left the country worse off than ever.

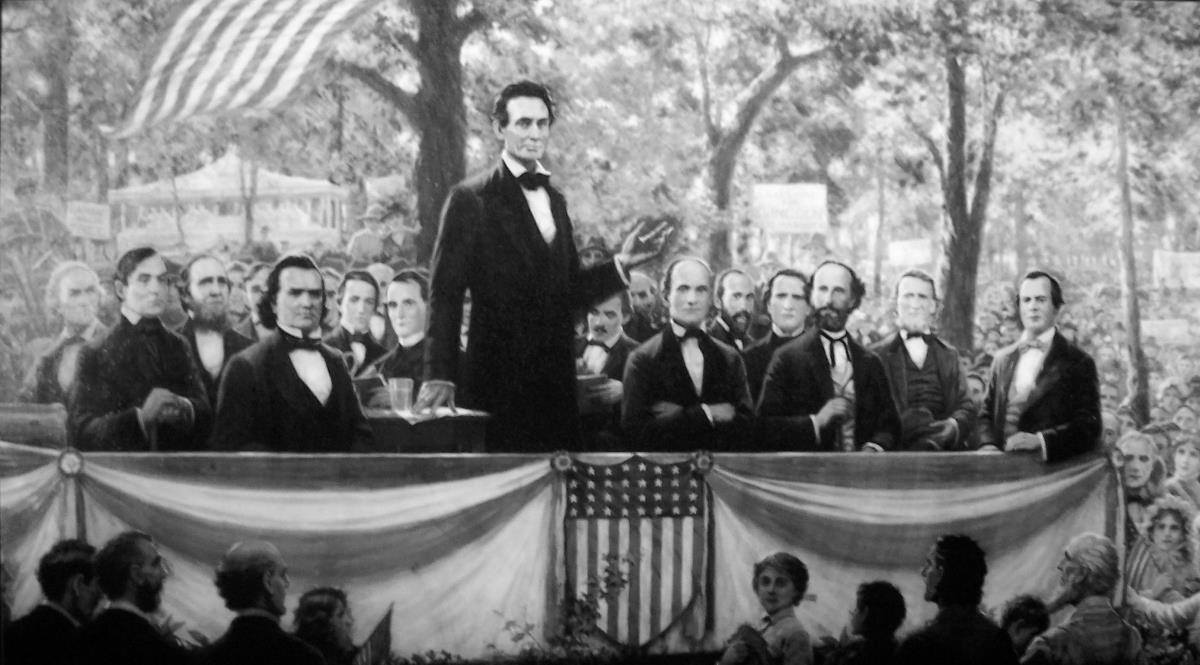

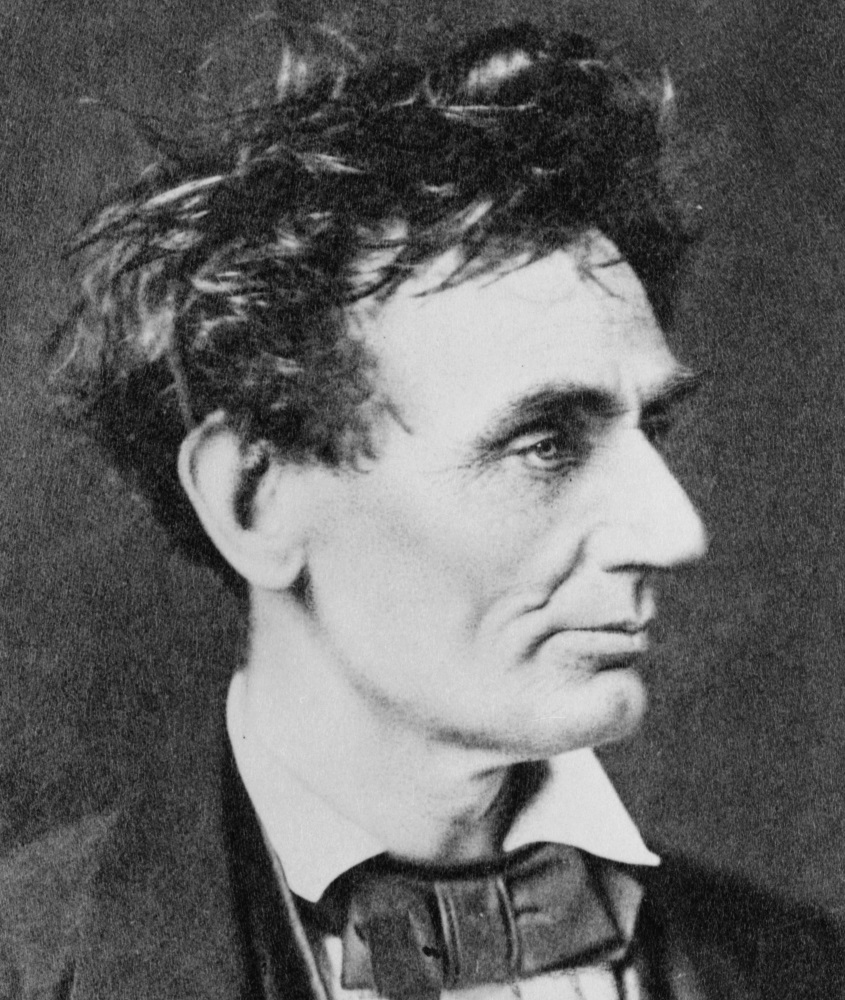

Lincoln. But with one president after another kicking the can of slavery down the road for his successor to deal with, the matter would come to a serious effort at resolution with Abraham Lincoln. And "serious" meant exactly that. And the South itself, having listened in on his Illinois Senatorial debates earlier with Stephen Douglas (1858) understood what would be coming at them if Lincoln, running as the Republican Party presidential candidate in the 1860 elections, were to gain the U.S. presidency.

The Southern states announced that if Lincoln won the election, they would simply secede from the Union. And indeed that's exactly what happened.

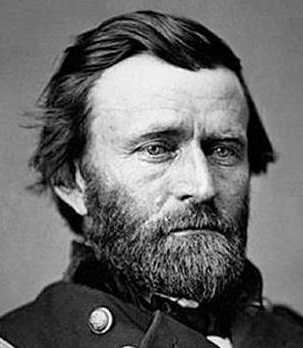

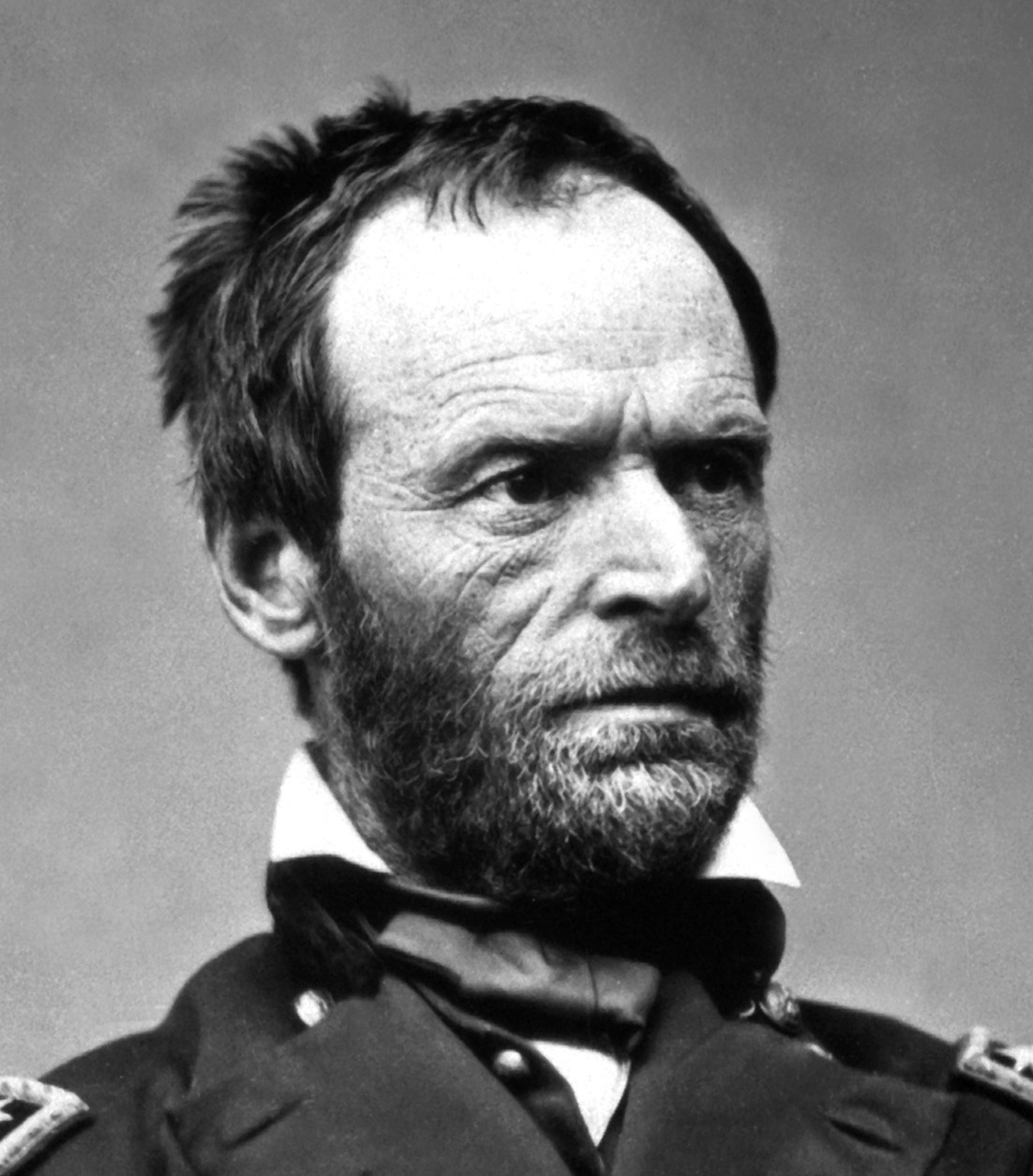

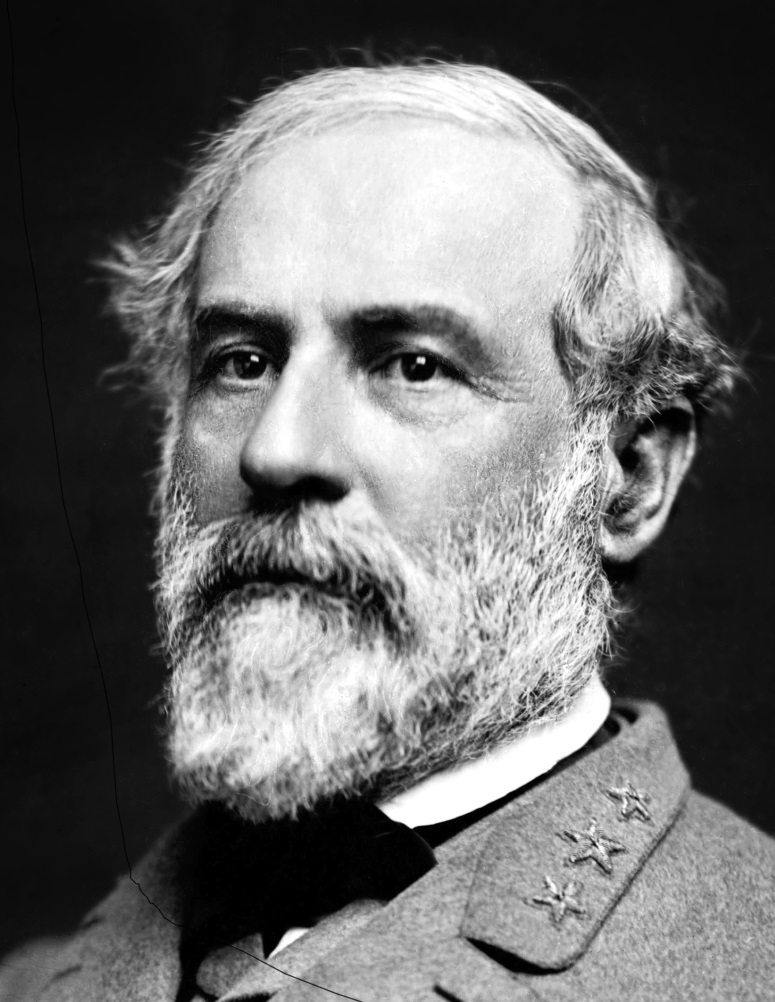

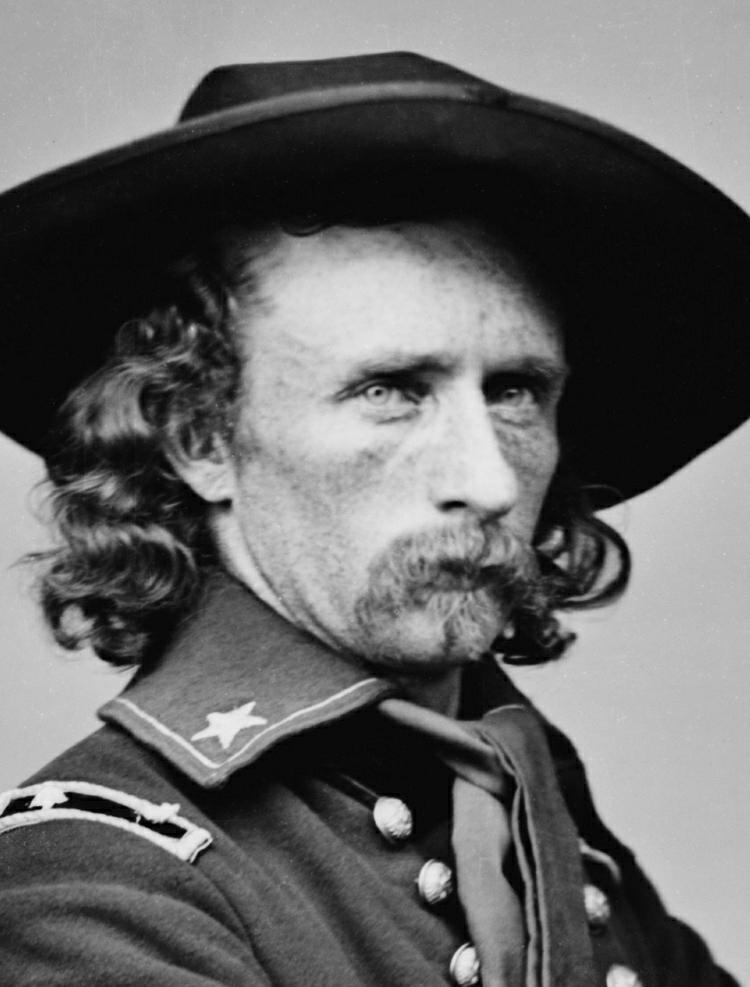

But Lincoln was no "country bumpkin" that they found themselves up against (as even some of his own cabinet members at first considered Lincoln to be). Like Washington, Lincoln was a man of deep resolve to do whatever was necessary to carry out the responsibilities placed on his shoulders as president of the Union. He was no mere politician looking to please the masses so as to get reelected in the next election. What he knew he had to do would be pleasing to no one, not even some of his generals (just as Washington found the case to be) who saw personal glory only in military combat, unaware of what it really took to win a war – something that would take much more than merely winning a number of glorious battles. Lincoln had a full war and not just battles to win – a Southern resolve to break – in order to put the Union back together. And Lincoln understood the economic and spiritual battles that would have to be fought, right alongside the military battles, in order to break that Southern resolve. Finding generals who would join him in that understanding would not be easy. In fact it was not until two full years into a very disheartening war that Lincoln was able finally to do so: his battle-tested Generals Ulysses S. Grant, William T. Sherman, George Thomas and Philip Sheridan.

But Lincoln was no "country bumpkin" that they found themselves up against (as even some of his own cabinet members at first considered Lincoln to be). Like Washington, Lincoln was a man of deep resolve to do whatever was necessary to carry out the responsibilities placed on his shoulders as president of the Union. He was no mere politician looking to please the masses so as to get reelected in the next election. What he knew he had to do would be pleasing to no one, not even some of his generals (just as Washington found the case to be) who saw personal glory only in military combat, unaware of what it really took to win a war – something that would take much more than merely winning a number of glorious battles. Lincoln had a full war and not just battles to win – a Southern resolve to break – in order to put the Union back together. And Lincoln understood the economic and spiritual battles that would have to be fought, right alongside the military battles, in order to break that Southern resolve. Finding generals who would join him in that understanding would not be easy. In fact it was not until two full years into a very disheartening war that Lincoln was able finally to do so: his battle-tested Generals Ulysses S. Grant, William T. Sherman, George Thomas and Philip Sheridan.

But there was more to the effort than just finding the right generals. Lincoln had to keep his American supporters in the North with him through those very dark days. Americans called on to kill fellow Americans was not something that they took on easily. And there were always politicians who were ready to take advantage of the political opportunities for themselves personally to play on the hurt and uncertainty Americans were experiencing as they went through this blood-bath. Even Lincoln's wife wanted him to just let the South go – so that they could get their family back to something like normal. Lincoln thus had a huge burden to carry to get America through this time of national testing.

But he did not do it alone. Although going into the White House, his reliance on God was no more than that of the "typical" Christian, the call to undertake these huge responsibilities brought him step by step higher – much, much higher – in his walk with God. Ultimately it was to God, not man, that he looked to keep his vision clear, his resolution intact, and his wisdom in handling day-to-day decisions at an almost super-human level. Gradually those around him came to realize that there was someone very special leading their nation.

Ultimately all the right pieces got put in place, and bit by bit the South and its "secessionist" resolve melted away. It was a very nasty process. As General Sherman himself put it: "War is hell." (Westbow Press, however, would not let me include this quote in my book!) And it was hell. Sherman intended it to be so. Very deliberately did he cut a 60-mile wide path of destruction as he swept through Georgia on his way to Savannah. The purpose was not only to feed his soldiers off the bounty of the land they were conquering, but ultimately break the spirit of the Confederacy. At the same time, off to the east in Virginia, General Grant and his troops were locked bulldog-style onto Lee and his troops, unwilling to let up after a battlefield victory – as had been the habit of the other generals (such as George McClellan). Now Lee could find no rest – and knew that he was facing an enemy that, with Grant leading it, would slowly grind him down until there was no fight left in his own army. That took some time for Grant to accomplish fully.

But finally, at Appomattox Court House, Lee had to give up the struggle. With Lee's surrender on April 9, 1865, for all practical purposes the war was over.

In the meantime Lincoln also was able (by the 13th Amendment being finally approved by both houses of Congress in January of 1865 – and ratified by the states later that year in December) to bring slavery to an end in America.

The cost had been horrible in terms of the lives lost by hundreds of thousands of young men. Unfortunately this is forgotten today when Whites are remembered as the source of slavery – but not at the same time remembered as the self-sacrificing souls that ended that horrible institution. No other people paid such a high price (including even the loss of Lincoln himself on April 15th) to bring slavery finally to an end in their country.

The post-war world of "Reconstruction." The assassination of Lincoln would leave the nation not only gasping but furious ... feeding the Radicals (strong anti-Southerners) to be even less merciful than they were inclined to be before the assassination. Not only did this incredibly socially self-destructive act by this wannabe Southern hero assassin Booth serve only to increase the North's wrath and desire for revenge, it took out the one individual who had the moral leverage to get America past the deep hurt everyone was feeling at that point ... and on to social forgiveness and renewal, much needed by the nation at that point. But that was evidently not to be.

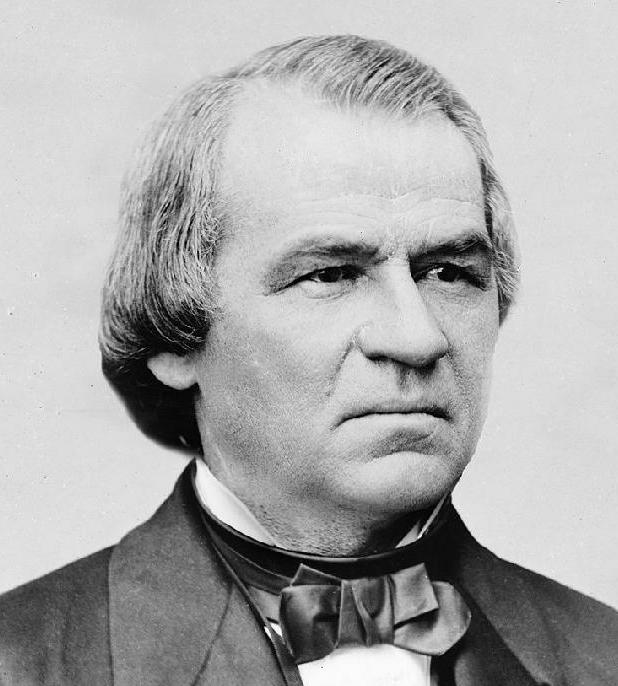

And the efforts of now-president Andrew Johnson to follow Lincoln's efforts at reconciliation were viewed by the angry Radicals as being treasonously pro-South (Johnson was after all a Tennessean). Soon Johnson was to discover what it was to try to lead a country with no serious power-base of his own. Whatever his ideas were, they were going nowhere without power-support. Ultimately Congress took off after Johnson for violating a Federal law making it illegal for Johnson to get rid of any of Lincoln's cabinet members that he had inherited in taking office (Johnson wanted to replace the troublesome Stanton with Grant as secretary of war). This was of course a law of very questionable constitutional legality, but one which served nonetheless to go after Johnson, claiming his violation of that law as grounds for impeaching him for having committed "high crimes and misdemeanors." This was an unprecedented use (but then not the last time, by any means) of the power of Congressional impeachment for purely political purposes.

And the efforts of now-president Andrew Johnson to follow Lincoln's efforts at reconciliation were viewed by the angry Radicals as being treasonously pro-South (Johnson was after all a Tennessean). Soon Johnson was to discover what it was to try to lead a country with no serious power-base of his own. Whatever his ideas were, they were going nowhere without power-support. Ultimately Congress took off after Johnson for violating a Federal law making it illegal for Johnson to get rid of any of Lincoln's cabinet members that he had inherited in taking office (Johnson wanted to replace the troublesome Stanton with Grant as secretary of war). This was of course a law of very questionable constitutional legality, but one which served nonetheless to go after Johnson, claiming his violation of that law as grounds for impeaching him for having committed "high crimes and misdemeanors." This was an unprecedented use (but then not the last time, by any means) of the power of Congressional impeachment for purely political purposes.

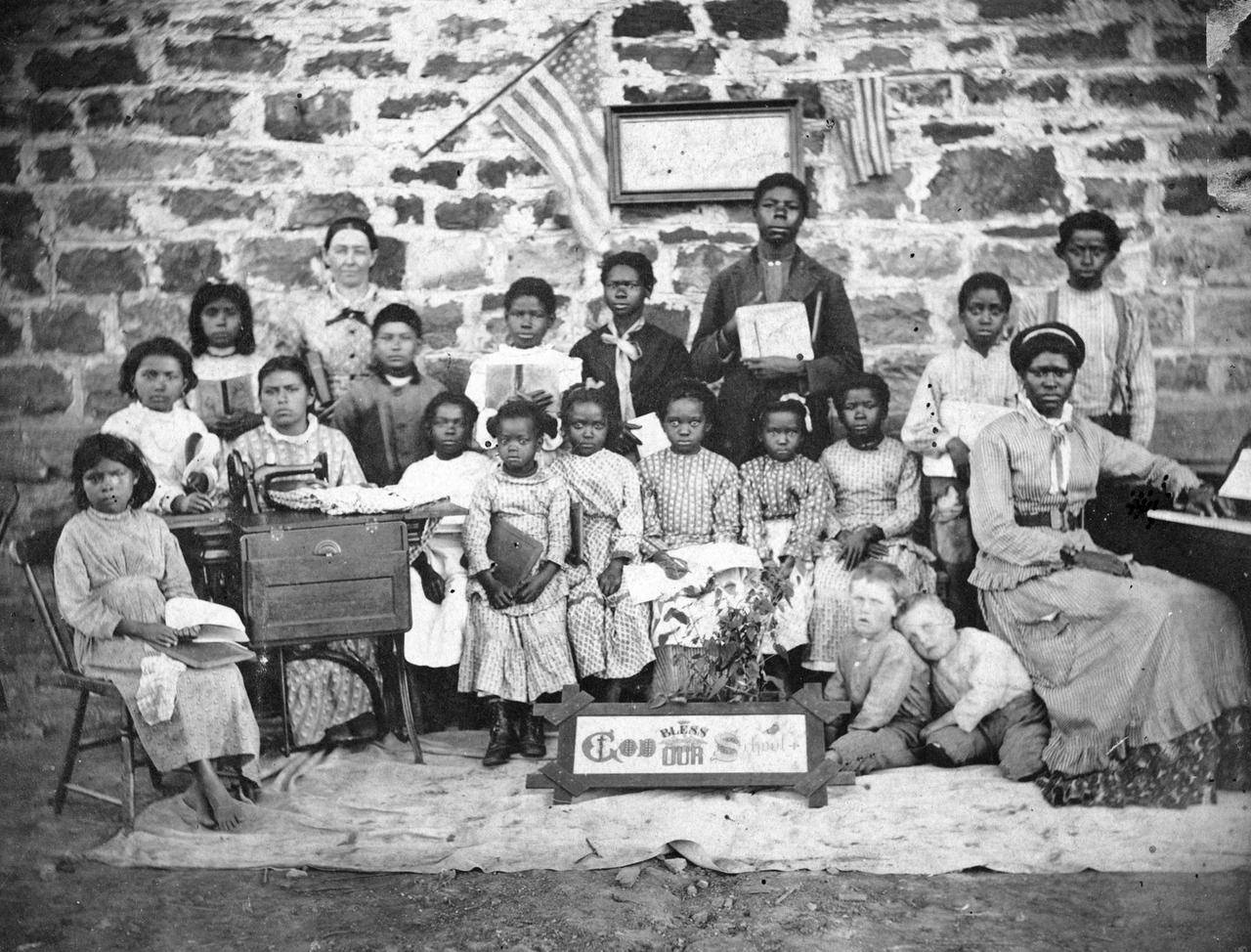

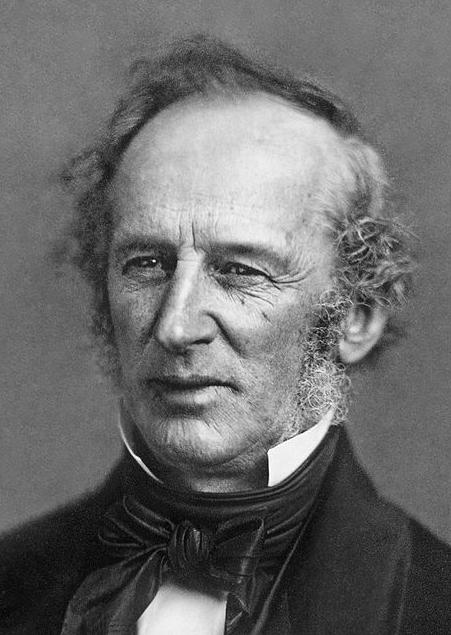

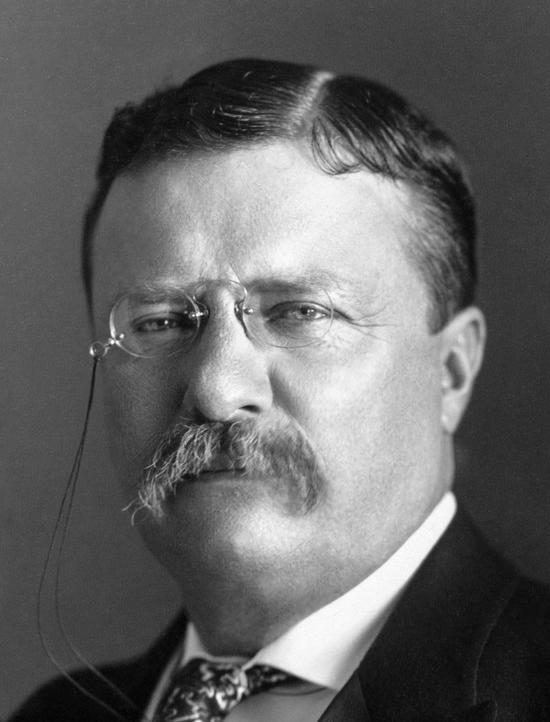

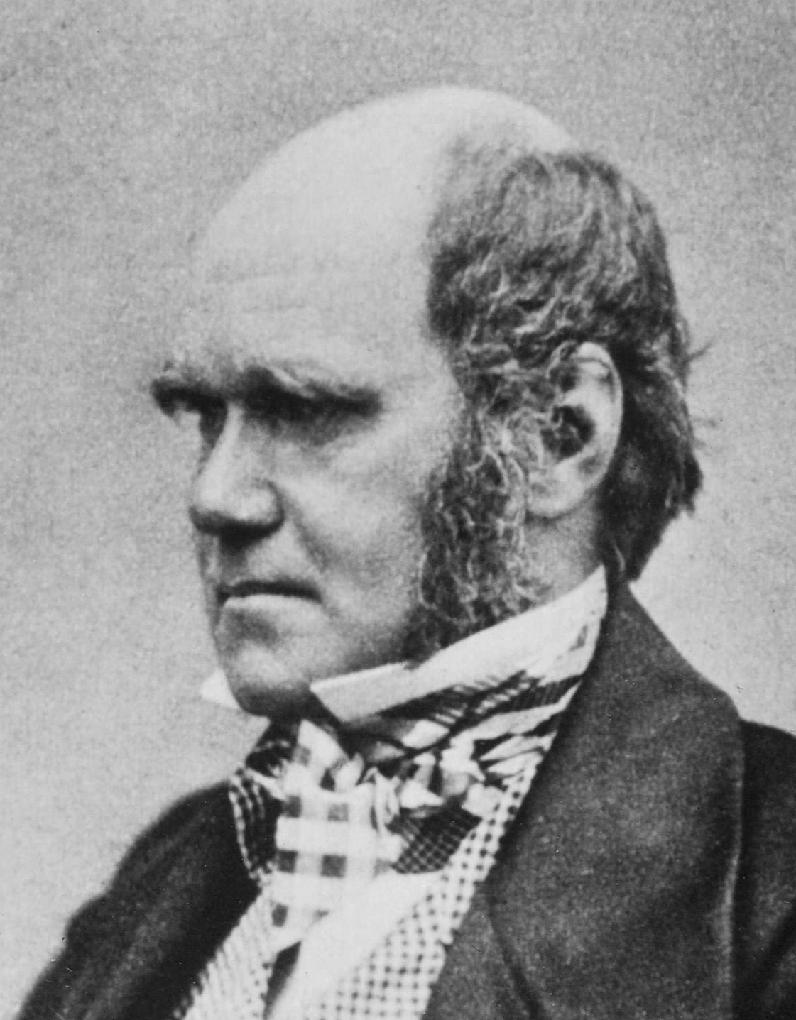

Ultimately the Radicals could not swing enough votes in the Senate to dump the defenseless Johnson. But after that, he effectively had no power as U.S. president. This then allowed the "enlightened" Radicals to run the country from Congress. This would be of no help to the country get past the hurt of war and on to new challenges.